{youtube}yQ7bXAgVW7E{/youtube}

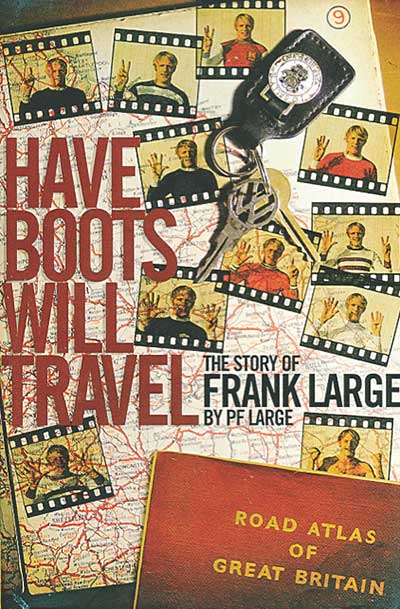

The story of Frank Large

The story of Frank Large

by P F Large

Pitch Publishing, £17.99

Reviewed by Alan Fisher

From WSC 336 February 2015

Growing up in the early 1960s, I got to know the players not through television or the papers but via my collection of bubble gum cards. On the front was a colour photo of my heroes, I devoured the brief biography on the back. Many times I shuffled the pack to create imaginary teams but one man always led the line.

Frank Large was the epitome of what I believed a centre-forward should be. Rock solid, over six foot tall, his rugged face battered, I presumed, from aerial battles with similarly uncompromising defenders. The right attributes too: “Honest, works hard, good in the air.” False nines, a pivot, mobile and pacy, I get it, times have changed but that image remains.

Large played for nine League clubs between 1958 and 1973, a total of 629 appearances including three spells at Northampton Town. His career spanned four divisions and he scored goals in all of them, well over 200 in total.

Large’s assessment of his talents is characteristically straightforward: “I can only do one thing but I’m good at it.” The story of this engaging, open man is lovingly told by his son through match reports, personal memories and interviews with ex-pros and managers, including his boss at Fulham Bobby Robson, who speaks with the humour and tenderness that footballers of a certain generation reserve for team-mates who they respect as a professional and friend. There’s a theme though – knock it up to Frank, Frank gets on the end of it, Frank never gives up.

Managers wanted him, often to give that extra push for promotion or to stave off relegation. Yet he was also easily dispensable as these same managers looked to upgrade. In 1966 alone he played for Carlisle, Oldham and Northampton. If he had regrets, he seldom showed them because this proud man was grateful for the chance to play.

There’s no in-depth analysis but the many anecdotes portray the life of this football man as a world away from that of today’s top professionals. Arriving at Halifax, his first club, he looked so bedraggled the other players gave him clothes. His reward for a cup run with Northampton was four new tyres for his second-hand turquoise Mini Clubman. There are many more and enjoyable they are too.

Perhaps the most telling insight comes when the game has finished with him. Returning home after his first morning in a factory, lungs and eyes chocked with toxic dust, he vows never to return yet picks himself up and endures the Dickensian conditions, 60 hours a week for 11 years, to provide for his family.

Frank Large died in 2003 aged 63, content in retirement in Ireland. His son’s readable, pleasing account does ample justice both to his father and a bygone age of football. Then again, Large will always be fondly remembered by supporters across the country as much for his wholehearted approach as for his goals. One of his most important for Leicester in Division One is described thus: “Frank slides in on his arse and crashes a shot into the top corner.” That’s my kind of centre-forward.

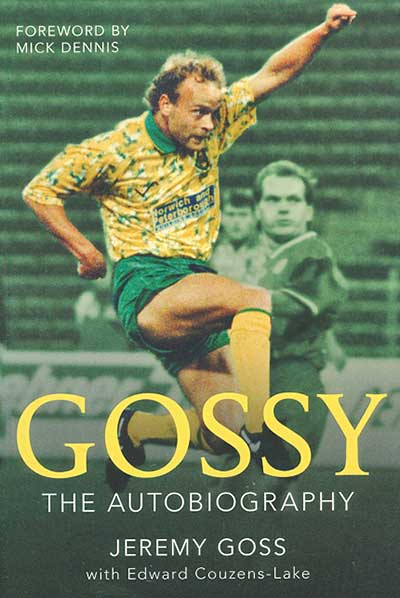

by Jeremy Goss with

Edward Couzens-Lake

by Jeremy Goss with

Edward Couzens-Lake

Amberley Publlishing, £12.79

Reviewed by Paul Buller

From WSC 336 February 2015

Jeremy Goss is not a player who can claim to have had a long and illustrious career. He did, however, light up English football in Europe after its very darkest days and brought myself and other Norwich City fans two seasons of sheer pleasure, the like of which we’ll probably never experience again.

Best known for his UEFA Cup goals in 1993 that helped Norwich become the only English side ever to beat Bayern Munich at their Olympic stadium, the midfielder briefly became a household name. His rise to fame, however, was as much a surprise to him as it was to those of us in the stands at Carrow Road who’d watched him endlessly trudge up and down the sidelines hoping to get a game.

Goss’s story charts his time in the wilderness very personably and it’s hard not to feel for him. Stuck in the reserves at Norwich for ten years, to this day he holds the record for most consecutive picks as first-team substitute (18). He doesn’t drink, he rarely goes out with the lads and he trains harder than anyone at the club. He’s sick of hearing managers tell him “Your time will come, son”. Yet every time he tries to move clubs, Norwich give him a new contract.

Perversely then, things work out for him just at the point he’s decided he doesn’t care anymore. He has become so sick of Andy Townsend getting picked ahead of him that he decides to go off the rails and enjoy a few pints, get a bit lippy around the training ground and nastier on the pitch. Enter the new manager, Mike Walker, who tells Gossy he’s going to build the team around him. And he does. Goss becomes an integral part of a Norwich team who start the season by beating Arsenal 4-2 at Highbury, are eight points clear at the top of the inaugural Premier League in December and finish in third place having qualified for the UEFA Cup.

On top of this he starts scoring spectacular goals – namely 20-yard volleys that win him goal of the month on Match of the Day, an honour he is almost childishly (and touchingly) proud of. A season in Europe ensues and Goss plays his huge part in creating history. He and the team believe they’re going to win the UEFA Cup and only Inter put a stop to it in the third round. And then his career crumbles as suddenly as it rose. Walker leaves for Everton, players are sold, Goss is back in the reserves.

Tales of banter are refreshingly scarce; this is a story of how hard work, dedication and an incredible belief gave Goss and his team their just rewards at a time when football was still more about competition than money. Gossy is a proper story and an interesting insight into what a footballer is actually paid to do – train, work hard, play and win. And he enjoys it. At the end of the book, whether you’re a Norwich fan or not, you can’t help but admire the man.

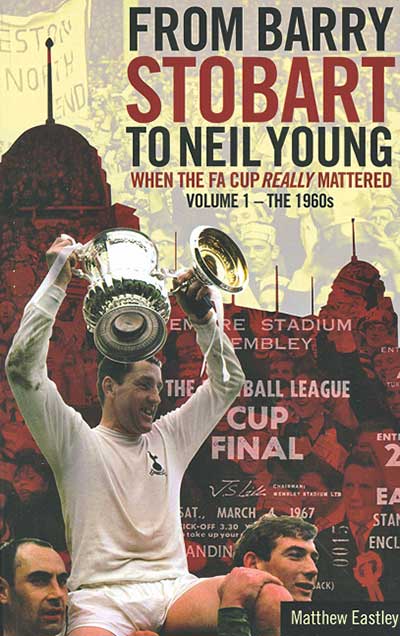

From Barry Stobart

To Neil Young

From Barry Stobart

To Neil Young

When the FA Cup really mattered vol 1 – the 1960s

by Matthew Eastley

Pitch Publishing, £14.99

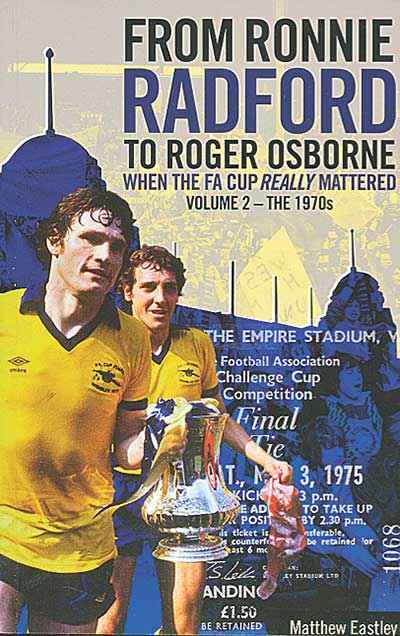

From Ronnie Radford To Roger Osborne

When the FA Cup reallymattered vol 2 – the 1970s

Pitch Publishing, £14.99

Reviewed by Adam Powley

From WSC 336 February 2015

There’s a game that’s been doing the rounds among fans of a certain age for a while. It involves being asked to name every FA Cup-winning club from a starting point – usually the mid-1960s – up to the present day. The respondent can invariably name each one, until he or she gets to the late-1990s, when all finals seem to blur into one boring, “Big Four”-dominated melange.

The point is to illustrate that the FA Cup is so obviously not what it used to be that it means we forget the recent past and savour the more distant. Memory can play curious tricks, however, and as Matthew Eastley shows, plenty of the finals during those supposed golden years of the 1960s and 1970s were far from being the classics of popular imagination.

For every totemic game and incident – Everton fan Eddie Cavanagh leaving pursuing police trailing in World Cup year, Chelsea battling Leeds in 1970, Sunderland embarrassing Leeds in 1973 (the best chapter in this double offering) – there are mediocre and pallid matches that undermined the final’s claim to its status as the biggest game of the season.

Yet the myths endure. Eastley writes extensively on every year in each decade, drawing on recollections of the fans who were there. Blended with references to newspaper stories and often laboured connections to hit singles of the day, the tale of each competition is told in present tense. The narratives are common: the thrill of the third round, building excitement as a Cup run gathers momentum and the agonising tension of semi-final day. The finals themselves express the wide-eyed wonder felt by supporters present for the great occasion, and the extreme emotions of victory and defeat. These really were games that mattered.

Other testimonies dare to contradict the orthodoxy. Hooliganism increasingly becomes a problem, even at finals. There are also the horrendous problems with ticketing and the annual disgrace that (then and now) saw loyal fans of competing clubs miss out while the touts enjoyed massive paydays. Eastley’s books do make some missteps. Many of the interviews read suspiciously like they were conducted via email, betraying a lack of natural conversational flow, and there is a lot of cliche. Clubs are “beloved”, Abide With Me sends “shivers down spines” and the experience, of course, is a “rollercoaster”.

But then FA Cup nostalgia is one big cliche. The competition’s rituals and customs have become the game’s liturgy, and its progress defined the rhythms of the season. League titles lacked the prestige and glamour of football’s great occasion. It was a Wembley FA Cup final everyone dreamed of seeing their team play in, and even if the old stadium was rundown as early as the 1960s, the whole event still rendered fans giddy and touchingly emotional.

Now, sadly, it is an afterthought, an inconvenience that gets in the way of the more lucrative Premier and Champions Leagues. The FA Cup is football from a different time and age – when, as Eastley delightfully shows, referees from Merthyr Tydfil named their house “Offside”, workmates generously strove to source a final ticket for a teenage colleague and fans could sing “Ee Ay Addio We Won The Cup” with sincere pride and not a hint of embarrassment. Eastley recognises the special place the Cup once had in fan affections and has created easy-going and perfectly justified wallows in nostalgia to suit.