{youtube}Sp3A54Hm66g{/youtube}

{youtube}ifW-F2koT4E{/youtube}

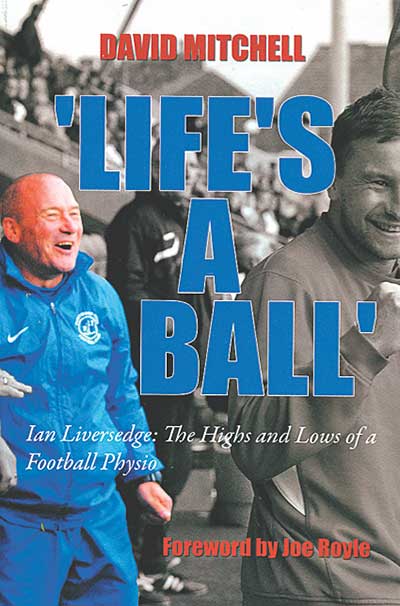

Ian Liversedge: the highs and lows of a football physio

Ian Liversedge: the highs and lows of a football physio

by David Mitchell

AuthorHouse UK, £10.95

Reviewed by Brian Simpson

From WSC 337 March 2015

Ian Liversedge had a long career as an itinerant football physio working for 20 clubs and 15 managers. The highlights are at the margins of his central story as he encounters famous people who played minor roles in his life. As a young player who didn’t make the grade as a pro he experienced the detachment of Everton’s legendary manager Harry Catterick and later encountered Brian Clough, in decline but still gracious in victory. A quote from Kevin Keegan in his playing days at Newcastle goes someway to explaining why striker Imre Varadi was on his way to accumulating 16 clubs: “OK, Varadi has scored 21 goals this season. I’ve set him up to score 60. How many times has he set me up? None. Fact.”

Less well known but vividly drawn is Accrington’s ex-chairman Eric Whalley. He had played for the club, managed them twice, taken a place on the board and eventually bought them. He funded player purchases but fell out with the local council about the cost of yoga classes for the club’s players. A major focus is the ten years Liversedge spent at Oldham from the mid-1980s, where the chalk-and-cheese chemistry of the taciturn Willie Donachie and the garrulous Joe Royle is captured well. His time at Newcastle also gives an insight into the management pairing of Keegan and Arthur Cox, yet very little of this is entirely new.

A desire to pack in as many stories as possible means that some topics don’t get followed up as fully as they might. For example, there are several incidental comments on the changes that have taken place in the treatment and medical care of players, but these are not considered in any coherent way. Some key points are better illustrated by a simple anecdote, such as when the gap between rehabilitation options at elite clubs and the rest is highlighted by noting that at smaller clubs his best option was sometimes to just take players for a walk and a coffee.

Towards the end of the book he describes meeting old friends from football when the conversation rarely touches on the game but is more about “the scrapes” they shared. But drinking exploits are the sort of tales that can only have been funny to those taking part and possibly not even then. Fans who followed Oldham in the period he describes might feel slightly short changed to find that many at the club followed a motto Liversedge characterises as “win or loose, have a booze”.

His description of players’ behaviour, and his own, is at least frank as he acknowledges its impact on his family life. But there is little reflection on whether the behaviour should have a place within any professional sport, nor an understanding of the way it feeds the negative stereotype of football held by many people. In the end, and despite the strengths of the book, his largely uncritical acceptance of some of what he saw or did leaves an impression in places of an opportunity missed.

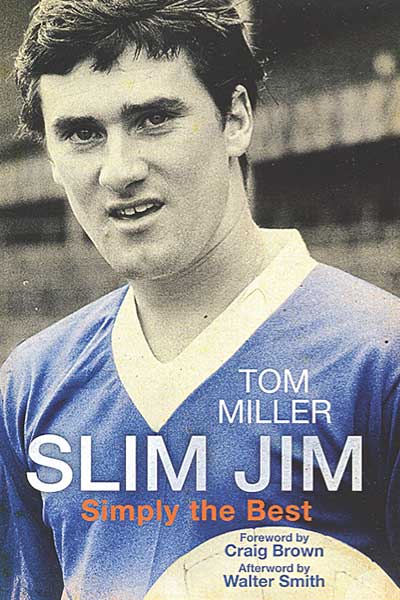

Simply the best

Simply the best

by Tom Miller

Black & White, £9.99

Reviewed by Gordon Cairns

From WSC 337 March 2015

The radio football parody Only An Excuse captured the Scottish perception of Jim Baxter almost to perfection back in the 1980s. His character explains his most famous performance, against England in 1967 where at one point he juggled with the ball: “I had a couple of great teachers… and three White & Mackays and a double Grouse, before I went on the pitch, like. That would explain the languid fluidity.” Unfortunately, the only inaccuracy was the choice of spirit – Baxter preferred Bacardi over whisky. Tom Miller tries to expand on the popular caricature of an incredible footballer who loved a drink by offering an explanation for Baxter’s self-destruction in this new biography, with somewhat limited results.

James Curran Baxter is often described as Scotland’s greatest player but ended a 12-year playing career with only ten domestic medals, which was not a lot given that Rangers were the dominant team in Scotland for most of his time at Ibrox. Perhaps that is why his eulogists focus on individual performances, including two victories at Wembley and being picked for a Rest of the World select. However the extent of Baxter’s drinking and lack of training must surely limit claims that he was truly world class. Although alcohol abuse was rife in the football culture of the 1960s, it’s questionable whether you can consistently operate at the top level with high volumes of alcohol in your bloodstream – Pelé and Eusébio weren’t playing with hangovers.

It seems Baxter’s problem was that he simply didn’t value the natural ability that raised him out of the ordinary, his career a long attempt at sabotaging the skill he possessed. In the most interesting chapter, sports psychologist Tom Lucas examines how never being acknowledged by his birth parents as their son during his playing career may have affected Baxter. (He grew up thinking his real mother was his aunt, who he was raised by.) Lucas’s conjecture is that the pitch was the only place Baxter could escape from the pain of rejection by his mother while his womanising could be connected to his feelings of abandonment.

Published two years after what was billed as “the definitive biography”, the bulk of this book rehashes the well-worn tales of Baxter’s drinking, gambling and occasional footballing. Miller, an in-house commentator for Rangers, didn’t have to wander far in his choice of interviewees, the majority of whom seem to come from the club’s “family”, including current defender Darren McGregor and youth-team coach Davie Kirkwood, I assume because both had played for Fife clubs like Baxter, hardly justifying their inclusion. Baxter’s own voice is barely heard, yet for most of his playing career he wrote syndicated columns. Although ghost-written, surely a trawl through these would have unearthed something more relevant than how McGregor felt when he joined Rangers.

The inclusion of two poems and a selection of pen portraits from the back of football cards feel like fillers to make the book up to the required length. There is no interview with Alex Ferguson, who played alongside Baxter; Scotland’s greatest manager’s views on getting the best from Scotland’s most talented player would have been compelling. Neither is there any input from Baxter’s sons or first wife, which could have given greater insight into how he felt about family, especially if he had issues about abandonment.