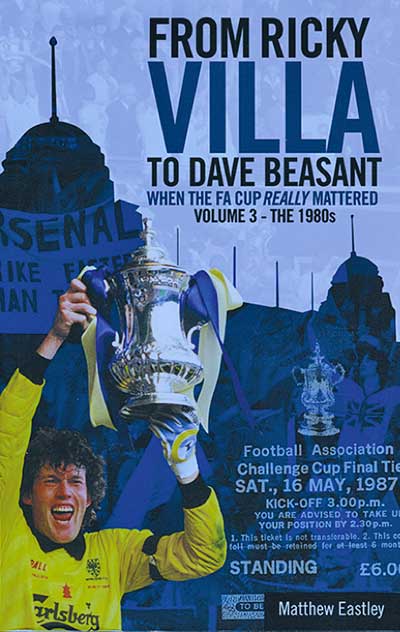

When the FA Cup really mattered Vol 3

When the FA Cup really mattered Vol 3

by Matthew Eastley

Pitch Publishing, £14.99

Reviewed by Jonathan Paxton

From WSC 342 August 2015

It’s hard to imagine Aston Villa or even Arsenal fans looking back on this year’s FA Cup final with much nostalgia but a dip into Matthew Eastley’s entertaining trip through finals from the 1980s is a pleasant reminder of why the competition’s heritage means so much to fans of a certain age. This was a time when Cup runs excited whole communities and smaller clubs had genuine hopes of reaching Wembley and lifting the famous trophy.

The stories, told chronologically from West Ham’s win over Arsenal in 1980, are recalled by fans in their own words and the absence of journalistic hyperbole is welcome. Interviews with supporters at Wembley on the day gives the stories a down-to-earth quality and fans of all clubs will understand quirks such as the West Ham fan who stuffs his Wembley ticket in his Y-fronts for safe keeping. Referencing hit singles and news stories of the day is a standard, if predictable way of placing the events in time but, by having fans recall the horrendous fashions of the era, we identify closely with them.

The other device used by Eastley is to revisit TV coverage of the day’s build-up and match. Cup final editions of Mastermind and It’s A Knockout are recalled with little affection and one wonders how Michael Barrymore blacking up to greet John Barnes at the Watford team hotel in 1984 was ever considered appropriate. Yes, we’ve all seen Ricky Villa’s goal and Gordon Smith’s miss but Eastley still manages to maintain some tension when describing matches and even the dire 1982 final is injected with drama. Some match reports (particularly from earlier rounds) do get a little stat heavy however and transcripts of John Motson’s commentary and basic descriptions of well-known action don’t add much to our knowledge of the matches. The occasional nugget does appear though: the tragic story of Welsh international winger Alan Davies (a winner in 1983 with Manchester United) is briefly touched upon and feels like it deserves its own book.

While there is no nostalgia for hooliganism, anecdotes of fans sneaking onto the opposing terraces are written with a sense of cheeky fun but descriptions of a dilapidated Wembley and crowd congestion are ominous. For those who fail to get tickets through the official channels, going directly to touts is seen as a perfectly viable option at the time and poor policing and stewarding is the norm. The author deserves great credit for his handling of the 1989 final.

Whether a supporter of the clubs involved or not, most fans will find something to identify with here. Those around at the time will enjoy the evocative memories but for younger fans, brought up on Sky coverage and all-seat stadiums, the sport may be unrecognisable. While it will probably find more warmth in Brighton and Coventry than in Liverpool or Manchester, this is an enjoyable retrospective of a time when Cup finals did actually stay long in the memory.