The two journalists have now passed away but their contrasting appreciations of the game will live on for many years to come

10 April ~ I see him at least half a dozen times a year, the bulbous middle-aged man in the beige anorak, swirly tie and Hank Marvin glasses. He stoops studiously in front of the teamsheet board, earnestly scribbling notes on a reporter’s pad, or tries to keep the remains of a side-parting in his wavy, greying hair as the breeze blows in off the clifftops. As he bustles past the stands, bulging nylon satchel beating against ankle-grazing slacks, he cheerily waves in acknowledgement at stony-faced codgers who have uttered no greeting. When the match starts he gabbles the breathless details of the action into a brick-like mobile at quarter-hourly intervals. “The crowd was on its feet in the 27th minute,” he says, his voice ascending to a Clive Tyldesleyesque crescendo-gurgle, though the only person I’ve seen rise from their chair since kick-off is the wife of one of the senior players when her Ugg boots got tangled with her French bulldog’s extendable lead.

“He doesn’t work for a paper, you know,” someone told me once, nodding in the bloke’s direction – he was in mid-flow, speaking into his phone as if addressing a faraway maiden aunt through a megaphone, squeezing unexpected melodrama from a goal-kick that went straight out for a throw. “It’s not switched on, that mobile.”

There was no criticism in the comment, I should add. After all, what is Step Six football for, if not to offer a safe and soothing haven to the lost, the lonely and the bewildered? There have been times in my life when, were it not for the reassuring sounds of a big-faced man with a voice like a hoarse beagle baying “Give over, liner” every five minutes, I’d have slipped the surly bonds of sanity myself.

One spring Saturday afternoon this month the non-reporter sat a few rows in front of me and went through his vivid calls and busy scribbling. Looking over his shoulder I saw the open page of his notebook, a frenzied diagram of player names in formation, criss-crossed with directional arrows. It was then I thought of Eric Batty.

In truth, the eccentric scribe and prophet of tactical-soccer-speak-yet-to-come had been probing my subconscious from a deep-lying position for some while. The death of Hugh McIlvanney had brought it on. Batty – who died in 1994 – was more or less the anti-McIlvanney. The Scot sought romance not intrigue from the game. To him football was not a puzzle to be solved, but an expression of character to be experienced. Batty, meanwhile, showed no more interest in the social milieu of the players, their personalities or the economic conditions that had forged them, than a chess player does on the origins of the wooden pieces with which he plays.

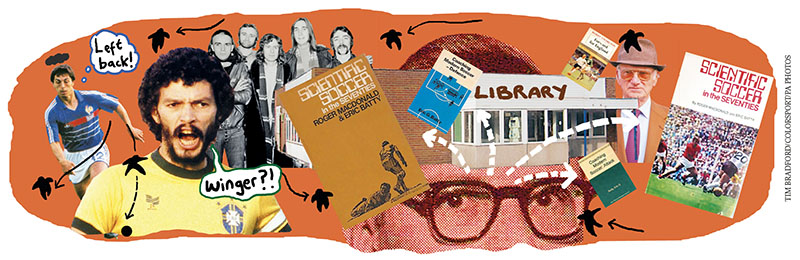

Every year in World Soccer the owlish technical expert would select his World XI, invariably slotting players into positions that were not their own (Alain Giresse at left-back, Sócrates on the wing). And why not? After all, they were pawns, he was Bobby Fischer.

Batty wrote for Soccer Star and World Soccer among others and by the mid-1970s was editing The International Football Book, which had first appeared in 1959 and by my own recollection devoted only a small amount of space to football outside the British Isles. Batty succeeded the original editor Tony Stratton-Smith who combined the role of football writer with managing The Nice, Van der Graaf Generator and Genesis, and founding Charisma records on which, among other things, he’d release an LP of Peter O’Sullevan’s favourite racing anecdotes. Stratton-Smith eventually retired from music to devote more time to trading thoroughbred horses.

The altogether less flamboyant Batty first came into my life when I was 12 and found a copy of his book Scientific Soccer In The Seventies in the village library next to Bobby Charlton’s autobiography. The cover title was done in the futuristic Westminster typeface suggesting the book – published in 1971 – was going to be 2001: A Football Odyssey, the sort of manual the telepathic children of TV’s The Tomorrow People might be reading as they passed the ball around at the back using only the power of the human mind.

Alas it proved to be a disappointment. The Brazilian team I had watched with wonder on morning TV highlights shows that seemed to be in vivid colour even on our black-and-white set had apparently won the Jules Rimet Trophy more or less by accident “virtually untried, untested and unchallenged” (in 1966 England had likewise “fumbled” their way to the title). The pages not filled with detailed analysis of the coaching dim-wittedness displayed in both success and failure, were covered in diagrams in which strangely abstracted players – starfish in shorts – danced about the pitch, their progress and destinations marked by a bewildering array of lines and arrows that made the whole thing look like the preliminary sketches of a Jackson Pollock canvas. Trying to make sense of them gave me a headache. I had hoped for enlightenment, but found only confusion and chaos. The non-reporter’s notebook looked much the same.

There is, as David St Hubbins says, such a fine line between stupid and clever. And perhaps the line between writing about football for a national publication and talking-in your expert opinion on the game from a windswept bench to nobody in particular is finer still. But then, you’d worked that out already, hadn’t you? Harry Pearson

Illustration by Tim Bradford with images from Colorsport/PA Photos

This article first appeared in WSC 386, May 2019. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more here