Examining how the phrase came to be so commonplace tells us a lot about the way in which the sport developed and spread around the world

24 August ~ For many football fans, the aesthetic qualities of a good match can rival those of any work of art. Long passes, clean shots, leaping headers and acrobatic overhead kicks are pleasing to the eye, as are the shifting movements of the teams’ formations within the simple white markings of the pitch. The phrase has become an over-used cliche (and, considering the various ills of modern football, an anachronism) but football has long been seen as a “beautiful game”.

Early match reports noted the “picturesque” appearance of contrasting team uniforms moving across “idyllic” playing fields. The movements of the players, even in a rough-and-tumble era of rudimentary tactics and formations, were an attractive fascination for early fans, and the pitches, despite mud and bare patches, were refreshing oases of green open space in football’s grey industrial heartlands.

The term did not originate in football, however. Victorian newspapers described billiards, lacrosse and cricket as the “beautiful game” before association football was codified. In 1863, shortly after the formation of the Football Association, Bell’s Life in London published a letter from Rugby School stating that rugby, not football, was “the most beautiful game that science can produce”.

Early uses of the phrase with reference to football generally described a performance rather than the game itself, in the manner of “Aston Villa have played some beautiful games this season”, and “Wolstenholme played his customary beautiful game”. Its first application to describe the game as a whole is generally attributed to HE Bates, the author of Darling Buds Of May. Writing in the Sunday Times in 1952, in an article headlined Brains in the Feet, Bates explained his opinion that “football is the most beautiful game in the world”. “I think we sometimes forget, or take for granted, the unique beauty of this game,” he wrote. “It is the only game in the world played with the feet. In its simplicity it makes a mockery of all the complicated paraphernalia of golf, or even the sly and contradictory subtleties of cricket.”

Broadcaster Stuart Hall subsequently claimed to have been the first to call football “the beautiful game” in his BBC radio match reports, although he has of course since been discredited in various ways. But the pioneering football journalist Jimmy Catton had used the phrase long before Bates and Hall. Catton wrote about “the spread of such a beautiful game as association football” in the Athletic News in August 1913. The influential Catton, who wrote his columns under the pseudonym “Tityrus”, shaped many of the conventions of football writing, but he did not popularise the use of the phrase.

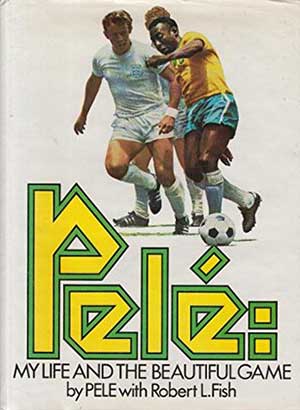

The earliest citation for it in the Oxford English Dictionary is from the title of Pelé’s 1977 autobiography, My Life And The Beautiful Game, and it is Pelé who popularised it. Subsequent references through the 1980s and beyond, whether celebrating the splendour of football or bemoaning its decline, have often reminded that “Pelé called football the beautiful game”.

He most likely borrowed and adapted it from his former Brazil team-mate Waldyr “Didi” Pereira, who is credited with originating the comparable Portuguese phrase “jogo bonito”. Didi, the playmaker who helped Brazil win the World Cup in 1958 and 1962, was describing the expressive and attractive style associated with the teams he played in, and later managed. Brazil favoured an attack-minded and free-flowing 4-2-4 formation, which became central to the jogo bonito philosophy.

After retiring as a player, Didi took this philosophy into management, leading Peru to the 1970 World Cup finals, at the expense of Argentina, and eventually losing a quarter-final against Brazil. He was subsequently appointed manager of River Plate, and successfully implemented the jogo bonito in Argentina, telling his players: “Let’s try to play a beautiful game.” (The Argentinian Diccionario del Football, published in 1971, contains the entry “‘jogo bonito’ as developed by Didi”.) However, after being accused of favouring style over substance, Didi quit Argentina for Turkey, where his approach won two league titles for Fenerbahce.

So “the beautiful game” is really a philosophy rather than a description, and its true meaning has its origins in Brazil. That meaning may have been lost in subsequent years, but the phrase is still used, for better or worse, to suggest an idealistic vision of a football that perhaps no longer exists. Paul Brown

This article first appeared in WSC 366, August 2017. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more details here