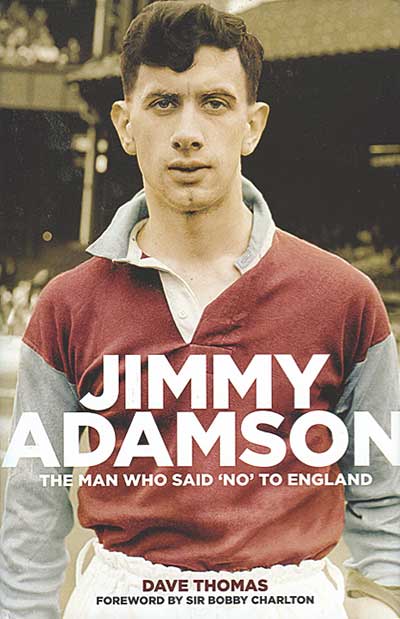

The man who said no to England

The man who said no to England

by Dave Thomas

Pitch Publishing, £17.99

Reviewed by Harry Pearson

From WSC 335 January 2015

Buy this book

Jimmy Adamson was born in Laburnum Terrace, Ashington, a few doors along from Bobby and Jack Charlton. All three would be Footballers of the Year. They shared character traits too; Adamson had Big Jack’s abrasiveness and Bobby’s tendency to aloofness. Unfortunately he didn’t have the charm of the former, or the diplomatic skills of the latter. The result, as lifelong Burnley fan Dave Thomas relates, in this illuminating and well told biography, was a career that promised much but ended in frustration.

Adamson’s childhood was brutally hard. His father abandoned the family at an early stage; his mother’s struggle to raise her children on her own ended in depression and suicide. Later he would suffer the horror of having his two children predecease him.

Whisked away to Burnley as a teenager after the north-east clubs took their traditional path of rejecting a local star, Adamson started as a winger but soon switched to half-back. Intelligent, tough, with a rare ability to pick a pass, he quickly became one of the stars of the team that took the League title in 1960.

As a coach Adamson was ahead of his time, a thinker and a tactician. After serving as assistant to Walter Winterbottom at the 1962 World Cup, he was offered the England manager’s job but turned it down to stay on at Turf Moor as player and eventually – after some backstage shenanigans to oust incumbent Harry Potts – the manager.

From Potts, Adamson inherited a side rich in young talent, labelling it “the team of the Seventies”. Unfortunately the economics of football had changed since his playing days and small-town clubs such as Burnley now struggled to compete with the big-city sides. The resulting financial pressures brought Adamson into conflict with Burnley chairman Bob Lord. Sitting in the head office of his butchery business in front of a large portrait of Winston Churchill, the man Arthur Hopcraft called “the Khrushchev of Burnley” was a self-made autocrat straight out of satire. (Indeed, one of the many entertaining nuggets the author has dug out is the fact that Brian Glanville wrote a sketch about Lord for That Was The Week That Was. Sadly it was never performed.)

As “the team of the Seventies” were dismantled to pay for ground improvements and fend off debt (and to line Lord’s pockets, it is alleged) the once close relationship between the two men descended into acrimony. “I wanted to build a team, the chairman wanted to build a stadium,” Adamson famously remarked after the split finally came.

Away from Turf Moor, Adamson never really settled. A spell at the side he had wanted to play for as a boy, Sunderland, ended after a couple of inconclusive seasons, the appointment at Elland Road in 1978 was fraught with problems from the off. By then alcohol seems to have blunted Adamson’s talent and exacerbated his prickliness. After Leeds he did not work in football again.

Adamson continued to live in Burnley, but was so bitter about his treatment by Lord he refused to go and watch even after his nemesis had departed. Thankfully he eventually made his peace with the club he had served so well. He received a warm and heartfelt ovation from Clarets fans on his return to Turf Moor. It gave some semblance of a happy ending to a life marred by rancour and loss.

Buy this book

The man who said no to England

The man who said no to England by James Ruppert

by James Ruppert The father of modern English football

The father of modern English football