An extract from a new book about the 1966 World Cup looks at how exotic visitors to that tournament inspired England’s own fans to travel abroad

29 June ~ The England squad that travelled to the 1962 World Cup in Chile had to endure a flight with two separate changes to Lima where they played a warm-up game against Peru before moving on to Santiago, then Rancagua where they would play their group games and then bus to their base at the Braden Copper Company staff house in Coya, some 2,500 feet up in the Andes. The journey of over 7,500 miles would have taken them more than twenty four hours. Hardly an ideal preparation for the tournament.

Very few fans could afford the high cost of travel (around £4,000 in today’s money) or the five-refuelling-stop flight on a BOAC Comet, meaning that England played their games in the Estadio El Teniente in Rancagua in front of fewer than 10,000 locals. Today, that same journey would take thirteen hours and cost £500, with no stops. On the basis of England’s travelling support in the past twenty years several thousand would now follow the team should they play Chile away.

When Walter Winterbottom’s squad left for Chile in 1962 it was from the Oceanic Terminal at London Airport. Four years later, when the squads for the 1966 tournament landed on English soil, the airport had a more familiar ring to it – Heathrow. It would be from departure points like this that the shift in our boundaries as fans would start.

The travel revolution was still a couple of decades away when the 1966 World Cup kicked off on 11 July with the hosts taking on Uruguay in front of nearly 88,000 but there is no doubt that the staging of the tournament in England changed the perceptions of whole communities in terms of overseas visitors, the likes of which many English people had never seen before. If the North Korean, Argentine and Mexican fans could travel halfway around the world to support their countrymen then so could England football fans.

It would however be a further sixteen years before England fans got the opportunity to really experience what it was like to be a football tourist. Four years after the tournament in England, Mexico offered better opportunities for the travelling fan than Chile ever did, but still the cost and the misguided perceptions created by the media of what visiting foreign countries was really like restricted the number of supporters prepared to travel.

However the 1970 World Cup did see the first attempt to create an official England supporters’ travel club for those now intending to follow the team overseas. The England Football Supporters’ Association offered members who wanted to travel to Mexico the opportunity to travel on an organised trip to watch the tournament, with transport, hotels, a full English washed down with pints of Watney Ale.

The downside? Fans would need to part with between £230 and £250 per person for a three-week trip, or around eight weeks’ money for someone on the then average UK wage of £32 per week, around £7,500 in today’s money. Britain was on the verge of a recession, after the “never had it so good” 6os. The typical demographic of football fans at the start of the decade was more likely to spend their money on a new Ford Cortina or Teasmade for their semi-detached in suburbia.

English football in the intervening years between 1970 and our next appearance in Spain in 1982 went through a radical change. To many, the watershed moment in the development of a culture of following club and country came two years earlier at Italia 80 when England qualified for the new-look European Championships. Thousands of fans travelled by plane, train and automobile to the group games. This was a new generation of football fans who had not previously had the opportunity to watch their nation play in an international tournament.

Many of these fans, only used to the passionate, sometimes unruly, terrace culture of England simply weren’t prepared for the way the Italian authorities treated them. With few having experience of watching football abroad, many didn’t adapt their behaviour and, faced with a new foe in the Italian police and the locals too, the English responded by running riot.

Despite the experience of being teargassed, or worse, two years later even more English fans headed to the 1982 World Cup in Spain. This was the first major tournament where a differentiated British national identity would come to the fore. All four home nations had previously qualified for the 1958 World Cup in Sweden but the travelling support for each was negligible in numbers, so no such impact occurred back then.

In Spain, whilst the English fans would still doggedly wave the Union Jack, the Scots and the Northern Irish defined their support as “anyone but England” and would continue to do so from that point on. The Scots and Northern Irish, perhaps not weighed down with the expectations of a nation on the pitch, made the most of their time in the sunshine off it, while the troublesome reputation that wrapped itself round England at Italia 80 was resurrected once more across the tournament at Spain 82.

That reputation stayed with England for a number of years, and was one of the main reasons why their group games in the 1990 World Cup were held on the island of Sardinia. The Italian police felt that containing the fans in one place for the first part of the tournament would be a benefit for all. Despite scraping through the group, England woke up in the knock-out stages. Of course penalties were our undoing in the semi-final but the national team had acquired a new and potently positive identity amongst the fans, many new to the game, and crucially amongst the media too back home.

A few years later the creation of the Premier League and the commercialisation of the game started to take hold against the backdrop of new stadia and this new generation of post-1990 fans. Interest in following England abroad grew off the back of another impressive performance in Euro 96. With the next two major tournaments taking place over the Channel in France in 1998 and then Belgium and Holland in 2000, thousands of new fans started to use the internet to take advantage of airline revolutionaries such as EasyJet, Ryanair and Buzz.

By Euro 2004, in Portugal, the last remnants of trouble were ebbing away. England fans began to be spoken of in the same tones as the hitherto friendlier Scottish and Irish fans. While there was the odd minor incident responded to by over-zealous policing, it was the England team who often let the side down now rather than the fans.

By Euro 2004, in Portugal, the last remnants of trouble were ebbing away. England fans began to be spoken of in the same tones as the hitherto friendlier Scottish and Irish fans. While there was the odd minor incident responded to by over-zealous policing, it was the England team who often let the side down now rather than the fans.

Despite the way they have been treated by police, demonised by the media, and on occasion disowned by their own FA, at the merest hint of a friendly somewhere abroad, thousands of fans will be logging on to flight comparison websites and finding the cheapest, if not always the most direct, route and booking it “just in case”. If these rumours turn into truth the earlybirds can pick up a bargain. In truth, when following England these days, the final destination is relatively irrelevant. In fact for many the more unfamiliar the place, the more attractive the trip. Stuart Fuller

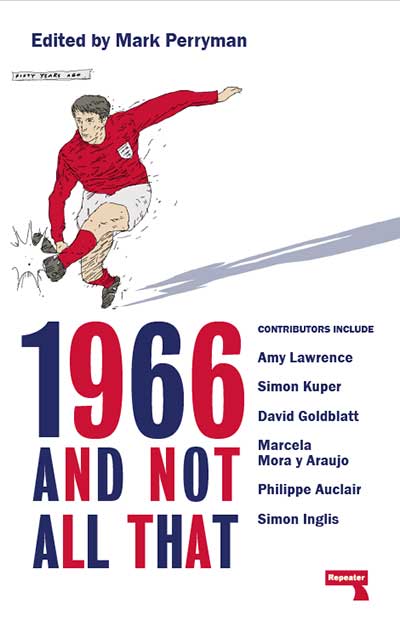

1966 And Not All That is out now from Repeater Books, £8.99. WSC readers can get the book for £7.99