Search: ' Matt Busby'

Stories

Bill Shankly was not just a manager: he was a communicator. In WSC 205 Barney Ronay listened and was reminded of a thousand pale imitations

The greatest non-League FA Cup run of the past 100 years – until this season – could have been even better. In WSC 218 Ken Sproat explained why

The untold story

of a football great

The untold story

of a football great

by Rob Sawyer

De Coubertin Books, £18.99

Reviewed by Simon Hart

From WSC 340 June 2015

It was 30 years ago in March that Harry Catterick died after suffering a heart attack at Everton’s FA Cup quarter-final against Ipswich Town. Five years earlier, Dixie Dean had also died at Goodison Park yet unlike the nationally famous striker, Catterick’s achievements – building two League title-winning teams – are today largely ignored beyond Merseyside.

Rob Sawyer has sought to redress the balance in a well-crafted biography that begins with a foreword from Colin Harvey, part of Catterick’s 1970 Championship side. “Don Revie, Bill Shankly, Bill Nicholson and Sir Matt Busby all get mentioned as being the great managers of the era while Harry doesn’t,” says Harvey of a man who won as many Leagues and FA Cups as Revie.

It is with Shankly, though, that Harvey makes the most telling comparison. For half of his 12-year reign, Catterick’s Everton drew the bigger crowds on Merseyside yet as Harvey recalls: “The press enjoyed being courted by Bill Shankly, but Harry was an introvert and snubbed them.” This is the crux of his image problem. Here was somebody who refused to allow the BBC cameras in to film Match of the Day until 1967 and had none of the charisma of his rival. Catterick was an aloof figure more akin to a modern-day director of football who – as his players would joke – put on a tracksuit only when the TV cameras or chairman John Moores appeared.

To achieve this insightful portrait, Sawyer pieced together interviews given by Catterick himself along with reminiscences of players and journalists and contemporary press cuttings. Alex Young recalls the coldness of a man not interested in courting popularity, saying: “I never got a pat on my head.” He had a devious side too, lying to the press and his own players; he told midfielder Brian Harris, for instance, that rumours of Tony Kay joining were false, only to swoop later that day for a player who had helped his Sheffield Wednesday side finish Division One runners-up in 1960-61.

Yet while his 1963 title-winners, built with the largesse of Littlewoods tycoon Moores, were dubbed “cheque-book champions”, the vision behind his youthful 1970 team would fit most current ideas of how to play the game. It was a 4-3-3 formation with the “holy trinity” of midfielders Howard Kendall, Harvey and Alan Ball at its heart. Dave Sexton, then Chelsea manager, applauded him for succeeding with a “set of small players up front” and Catterick’s own view was: “When it comes to the creation of something in tight corners, which midfield men have to do, give me the little ones.”

His players might have endured an old-fashioned factory-style clocking-in system but his planning of Everton’s Bellefield training ground – with an indoor pitch for small-sided matches – was another demonstration of foresight. Indeed in October 1970 Charles Buchan’s Football Monthly magazine dubbed the then 50-year-old “a manager for the Seventies”.

Sadly for Catterick – and his legacy – his Everton team soon fell apart. Sawyer recalls a pivotal week in March 1971 when they lost a European Cup quarter-final to Panathinaikos and FA Cup semi-final to Liverpool. After Ball left in controversial circumstances and Catterick himself suffered a heart attack, he was sacked in 1973. Not until 1985, two months after his death, would Everton win the League title again.

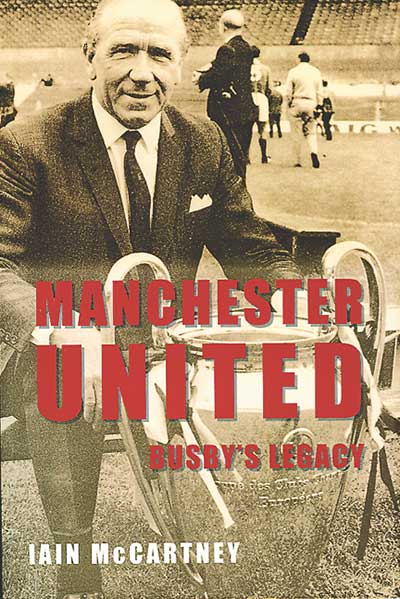

by Iain McCartney

by Iain McCartney

Amberley Publishing, £16.99

Reviewed by Charles Morris

From WSC 339 May 2015

A book about managerial succession and how a club attempts to replace an outstanding, long-serving supremo is timely, particularly in Manchester United’s case. Iain McCartney’s book follows his Rising from the Wreckage: Manchester United 1958-1968, which charted the club’s recovery from the Munich air tragedy to become the first English team to win the European Cup.

Rapid decline, however, is the theme of his sequel as he relates the club’s dismal failure to replace Matt Busby between 1968 and 1974 – when they were relegated from Division One – and to replenish the team of George Best, Denis Law and Bobby Charlton.

As a history of those six seasons it succeeds, but it seems a missed opportunity not to have broadened the format and considered other cases of managerial succession, particularly as United currently remain in a troubled transition from Alex Ferguson’s reign. Busby’s Legacy does, however, provide a case study in how not to handle such a handover. A tired Busby quit in 1969 after nearly 24 years that also included five domestic championships and two FA Cups. But he fatally remained as general manager and was allowed to choose his successor.

His choice of Wilf McGuinness proved disastrous – a history lesson ignored when Ferguson was allowed to select David Moyes. McGuinness, aged only 31, was Busby’s reserve team coach. He had no experience of managing a first team and was younger than some in an ageing United side, such as Charlton, Bill Foulkes and Shay Brennan. His authority was further undermined by initially being appointed only as “club coach” for an “unspecified probationary period”, and by the presence of Busby. The Scot kept the manager’s office while his successor was given a “corner cupboard”, and he later secretly tried to replace the hapless McGuinness with Celtic’s Jock Stein.

After McGuinness’s inevitable failure and removal in December 1970, Busby played a major part in the hiring of Frank O’Farrell from Leicester City. Although more experienced than his predecessor, O’Farrell’s record was “not trophy strewn”, including only one promotion with Torquay and an FA Cup runners-up and relegation with Leicester. Busby unsuccessfully tried the office belittlement trick on O’Farrell, too, and subsequently interfered in team matters.

One is tempted to conclude from these appointments that Busby, unconsciously, could not bear the idea of handing over to someone who might emulate his feats. After a disappointing 18 months O’Farrell was also sacked and replaced by Scottish national manager Tommy Docherty, who was unable to save the club from relegation before quickly restoring their fortunes back in Division One.

McCartney’s tale of a great team in decline for the most part rattles along, reminding us vividly of Best’s genius and his sad early fall into alcoholism, the complacency and ineptitude of United’s directors and the onset of two decades of appalling football hooliganism. It suffers, however, from an over-reliance on match reports, sticking only to the historic facts and dreadful editing. The book is littered with spelling errors and misused words, all of which are irritating and only one amusing: where the team’s performance is said to be “bisected with a fine toothcomb”. Readers paying £16.99 deserve better.