Bill Shankly was not just a manager: he was a communicator. In WSC 205 Barney Ronay listened and was reminded of a thousand pale imitations

In 1997 a plaque was unveiled in Glenbuck commemorating the 55 professional footballers the Scottish mining village produced during the last century. Among them was Bill Shankly accompanied, even here, by what have become his defining epithets: “the legend, the genius, the man”.

This seems to be more than just a localised view. “I watched his genius unfold,” wrote Tom Finney in 1993. “A great man, a great manager and a great psychologist,” enthused Kevin Keegan. No mention of Shankly, it seems, is complete without a magisterial turn of phrase. The legend, the greatest, the granditudelissimus – when it comes to Shankly we all turn into Don King.

Shankly’s achievements as a manager were undoubtedly great. Between 1959 and 1974 Liverpool won the League three times, the UEFA Cup once and the FA Cup twice, success achieved by reconstructing the club from within. When he was appointed Liverpool had spent the past five seasons in Division Two and, in his own words, “the place was a shambles”.

Shankly released 24 players in his first two years, but kept hold of the boot-room personnel – Joe Fagan, Bob Paisley and Reuben Bennett – who would remain at the club throughout its subsequent success. By the time he retired, Shankly had laid the foundations for 15 years of domestic and European domination.

Great, but not unique. His record is similar to that of Don Revie at Leeds over the same period. Revie also took a struggling club into Division One, building a team and a way of playing that brought two League titles, European success and a certain era-defining swagger.

Similarly, Herbert Chapman turned his Huddersfield Town side into the most successful team in the country during four mercurial years in the 1920s. Yet few outside Elland Road make a habit of hailing Revie’s genius, while the Terriers similarly failed to implant themselves in the consciousness.

Shankly’s genius exists outside his bare achievements. He remains a footballing archetype: an arresting, vivid, revolutionary voice. And one that refuses to die: at times it seems what survives of Shankly is a zombified anthology of quips, aphorisms and gags, still staggering from biography to website to after-dinner speech after all these years.

Everybody knows the quotes. “I want to build a team that’s invincible, so they’ll have to send a team from Mars to beat us.” “Me having no education, I had to use my brains.” “I don’t drop players, I make changes.” What was once fresh and startling has become fogged by layer upon layer of repetition. Was Shankly actually funny? Or just a compulsively wisecracking boss: a footballing David Brent, with Tommy Docherty as his Finchy?

Take this, for example: Docherty: “You have to say Tony Hateley’s good in the air.” Shankly: “Aye, so was Douglas Bader… and he had a wooden leg.” Or this: “If he had gunpowder for brains he couldn’t blow his cap off.” Shankly, like anyone, could be boorish: “The trouble with referees is they know the rules, but they do not know the game.” Or platitudinous: “If you are first you are first. If you are second you are nothing.”

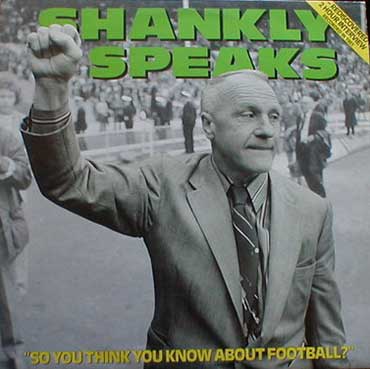

For the post-Shankly generation it is tempting to ask exactly why quotations such as these have been feverishly transcribed for the past 30 years. Shankly’s genius, on the cold hard page, eludes us. What we need is Shankly the voice. And fortunately, the voice still exists – in the form of the gatefold double album Shankly Speaks.

Billed as “a feast of a listening experience”, Shankly Speaks showcases a lengthy interview recorded over two days at the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool in 1981. There is no preamble: as soon as the needle touches the record Shankly speaks, holding forth on what the sleeve notes describe as “producing great teams”. The voice is a nimble baritone, rapid but still languid.

In fact Shankly’s sentences have a distinct dramatic rhythm, which the voice seems to reach for instinctively. Talking about “the Liverpool system”, he says: “You need options, two people to take it off you. Three. Choices,” and it’s as though he’s outlining some magical formula. Pressed on the funniest moments during his time in the game, Shankly describes the older players at Glenbuck telling “exaggerated tales” to “lift away the gloom” and he laughs, a surprisingly childish gurgle. It’s a sound you want to hear again: conspiratorial and unselfconscious; in the laugh you catch a glimpse of Shankly’s talent for inspiring deep affection in those around him.

Later, talking of the need to drum instructions into players, he recalls, as he does elsewhere, a recorded message in a New York lift repeating the words “mind the stairs”. On paper the story doesn’t register; told in Shankly’s urgent tones, it seems keenly observed and startlingly relevant.

Shankly Speaks does exactly what it promises: Shankly does indeed speak. But rather than the trumpeted “insights”, what stays with you are the quality and rhythm of the voice. More than just a silvery phrase-maker, Shankly communicated a passion for the game, for a club and for a region never before expressed through the media. He spoke directly to the support of his own and every club, using not quite the language of the terrace but a hybrid of everyday speech and the wisecracking theatricals of a movie gangster.

Thus Shankly gave the manager his voice, creating a template for all the messianic Big Mals, Big Rons, Old Big ’Eads and Little Kevs that would follow, mostly limply, in his shadow. People didn’t talk about the game like Shankly before Shankly. After Shankly, everybody did, or could, or wanted to.

Genius is a difficult concept in sport. In his essay on the cricketer Garry Sobers, A Representative Man, CLR James provides a working definition of the word in a sporting context: “Geniuses are merely individuals who carry to a definitive extreme the characteristics of the special act or function which they express.”

The influences that found such vivid expression in Shankly are easy to trace. As a manager he was belligerent, tyrannical, wisecracking, but always affectionate – a Scots James Cagney or a South Ayrshire Philip Marlowe.

Of his own upbringing in Glenbuck during the inter-war years, Shankly said: “There were only two things in Scotland in those days: the pit and football. Football was better,” and like many of his generation Shankly had grown up watching depression era and wartime films from the US.

All of this would be reflected in his own public persona: the bluff façade of Cagney mixed with the wise-guy patter of Jack Benny or even, occasionally, Groucho Marx (“Just tell them I completely disagree with everything they say” – Shankly; “Whatever it is, I’m against it!” – Marx).

Like Benny, Shankly instinctively reached for a straight man. Hence his continual sparring with Everton. “This city has two great teams – Liverpool and Liverpool reserves,” Shankly quipped, putting an arm around the shoulder of his blue-shirted stooge and lighting a match off the back of his neck. “If Everton were playing down at the bottom of my garden I’d draw the curtains,” he cracked – and yet Shankly ended up coaching an Everton boys team; the relationship never soured, remaining an affectionately rivalrous double act.

It seems appropriate that his most celebrated quip was borrowed from an American. When Shankly said, in jest: “Some people say football is a matter of life and death. I’m very disappointed with that attitude. It’s much more important than that,” he was quoting Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi.

Shankly brought a US-style democratisation to the language of football. Where the pre-Shankly English manager was a mute, faux BBC-accented stammerer of platitudes, American sportsmen had a voice of their own and Shankly, by design or historical accident, brought this vernacular to football.

Shankly survives as the most living of dead managers. Matt Busby seems, for subsequent generations, a remote, slightly vicar-ish figure; but Shankly is vibrantly still with us. Titles and cups will always be won, but football’s most lyrical icon, whether on vinyl, in the Chinese whispering of a fan website, or in the post-match posturing of a Shanklyite managerial descendant, will continue to speak. Barney Ronay

This article was originally printed in WSC 205, March 2004. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more details here