With clubs getting desperate for overnight success, the concept of time is becoming an elusive commodity for managers

With clubs getting desperate for overnight success, the concept of time is becoming an elusive commodity for managers

Two managers have been booted out of Premiership clubs after three games of the season, and although no one is crying in the streets at the departure of Kenny Dalglish or Christian Gross, the circumstances of their dismissal speak volumes for the feverish state of the game.

Neither, on the face of it, had done a particularly good job, although Newcastle fans would need little reminding that before last season they had only appeared (“competed” is hardly the word for their 1974 effort) in one FA Cup final since 1955. Perhaps more significantly, neither man enjoyed a good relationship with the media, being perceived respectively as sour and dour. In Gross’s case his reputation was scarcely deserved – strangely though he may have behaved at times, he was always unfailingly polite and accessible, even to the reporters who repaid the favour by crucifying him daily in print.

Most of all, however, both failed to put teams out which were capable of living up to the self-image of the clubs concerned – attractive, free-scoring and, above all, glamorous. Dalglish suffered by comparison with his predecessor, Kevin Keegan, although fewer commentators were keen to invoke the attractive, free-scoring and glamorous sides put out by Ossie Ardiles to ram home the point.

Gross, of course, stood accused of failing to bring back “the glory, glory nights”, those memorable occasions when White Hart Lane throbbed with the thrill of putting exotic European opposition to the sword. When was that again? It was in the early 1960s, if we’re talking of Spurs teams winning championships, or the early 1970s when they reached the UEFA Cup Final twice in three seasons. Or was it the early Eighties, when Tony Parks made himself a hero behind a side that contained the flamboyant talents of Steve Perryman, Graham Roberts, Paul Miller, Mark Falco and Gary Stevens?

The point is not to knock those players or that team – after all, it won a European trophy when they were still worth winning. It’s rather that the image of each Premiership club has become a key factor in the ever more frantic appointment and dismissal of managers. Those images have always existed as a kind of subtext to football conversation, a handy set of key words which everyone understood but few ever bothered to examine closely (West Ham are supposed to be a football academy, Chelsea are required to reflect the supposed glamour of the Kings Road, and so on). But now they have become a public benchmark by which each new manager is to be measured.

Of course, such labels are often disregarded, as Tottenham’s pursuit of George Graham confirms. If they are successful, fine, but woe betide the misfit who fails in both style and results – they will find themselves as friend- less as Dalglish at Newcastle, Lou Macari at West Ham or Peter Withe at Wimbledon.

For the outsider, of course, the relentless harking back to various dubious “golden eras” by clubs such as Newcastle is an endless source of fun. And the further back any real success came, the more their image is subject to absurd revisionism of the type that tries to persuade us that United fans will tolerate nothing but a pastiche of the Keeganesque devil-may-care, damn-the-torpedoes philosophy. Yet some of them, surely, can still remember living through the Gordon Lee and Bill McGarry eras, not to mention 13 mostly mediocre years under Joe Harvey, during which they won their last trophy to date, the 1969 Fairs Cup.

But back then clubs and fans were prepared to settle for less. They craved trophies, of course, but if the team played some decent stuff and they finished around half way or above, few were prepared to call for the manager’s head. Most people realized, logically enough, that not everyone could win everything all the time.

Now that kind of half-success is no longer enough. The stock market, directors, the media and, rather pathetically, many fans, demand instant gratification. Managers who fail to deliver in style or content can be expected to last little more than a season if they are unlucky enough to land a club (and that’s most of them) where the board is collectively incapable of keeping its nerve.

Back in February 1990, Manchester United had gone 11 games without a win and dropped to 17th place in the table. Martin Edwards had already been rescued from one catastrophic decision that season – narrowly failing sell his shares to Michael Knighton for £1 million. Despite immense pressure to sack Ferguson, he somehow managed to get something else right, and clung on to him. Ferguson had already had four years to deliver the goods, a period of grace almost unimaginable for most clubs now.

It’s a lesson the rest of the League shows little inclination to learn, outside such cases of good sense as Crewe and Wrexham. Instead they rush from coach to coach in an increasingly frantic search for the man who fits their marketing and media image, and maybe even knows something about building a team as well. Who knows, perhaps Ruud Gullit will make us all look silly by leading a triumphant Toon Army to the League title. But if anyone should know about the perils of instant gratification, it’s the board of Newcastle United.

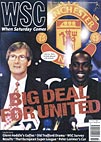

From WSC 140 October 1998. What was happening this month