Alex Ferguson has always let his political views be known, which is why Michael Crick is confused about the lack of it in his book

Alex Ferguson has always let his political views be known, which is why Michael Crick is confused about the lack of it in his book

It’s an interesting test. Just who in public life today could ring Downing Street at 7.30am and be put straight through to Tony Blair? Gordon Brown, Robin Cook or Jack Straw? Certainly. Rupert Murdoch? Undoubtedly. Middle-ranking cabinet members like Stephen Byers and David Blunkett? Pretty marginal, I’d say. As for ministers like Chris Smith or Clare Short, they’d probably be fobbed off by the switchboard whatever time of day it was.

But Sir Alex Ferguson, I understand, has no difficulty being put right through to the Blair quarters. For that’s what happened when the United manager rang the PM at breakfast time one day in late July to complain about Kate Hoey’s ill-informed attack on Manchester United’s decision to opt out of the FA Cup.

It’s a sign of Alex Ferguson’s special standing in the New Labour firmament. The knighthood conferred on him in June wasn’t just for winning the Treble or for United’s achievements in Europe, but also for Fergie’s sterling service to the Project. The United manager has regularly contributed to the party’s campaign efforts, and before the 1997 election gave Blair and his team private advice on how to keep their bodies in good physical shape while working long hours day after day (avoid all alcohol was one tip, despite, or perhaps because of, Fergie’s one-time career as a publican).

The winning of the European Cup was merely a convenient moment to deliver the knighthood – it probably would have arrived anyway in due course, even if Ferguson had failed to emulate Sir Matt Busby in lifting the senior European club trophy.

Few football managers have been more political than Alex Ferguson. He recently moaned about the government being dominated by Arsenal supporters, and while, quite remarkably, there doesn’t seem to be a single minister who is a United fan (the last one, Tony Lloyd, was axed in the latest reshuffle) probably no manager in the history of English football has been closer to Downing Street.

Alex Ferguson is friendly not just with Blair himself but extremely close to his powerful press secretary, Alastair Campbell, whose love of football is genuine (whereas Blair’s commitment to the game has always been rather suspect). Campbell and Ferguson are said to talk by phone at last once a week and often a lot more. But you’ll find none of this in Ferguson’s autobiography, Managing My Life. Indeed, neither Blair nor Campbell gets a single mention.

It’s a book, one might say, which Ferguson’s collaborator Hugh McIlvanney, himself a political animal, was destined to ghost-write. A couple of years ago McIlvanney presented a fascinating TV series on those three working-class Scots, Matt Busby, Jock Stein and Bill Shankly, all born within a few miles of each other in central Scotland, and who all reached their footballing pinnacles in the late 1960s. If anyone was their collective son it’s Alex Ferguson, the man at Stein’s side as he died of a heart attack on the night Scotland qualified for the 1986 World Cup, and, of course, Busby’s successor-but-five at Old Trafford.

Their Scottish socialist upbringings were important to all four men. For each manager their experience of real work before going into football full-time – the first three in the Lanarkshire coalfields, Ferguson as a Glasgow toolmaker – hardened them, taught them the value of collective effort, and fuelled the fires which propelled them towards their eventual triumphs.

Yet in his book the United manager touches only very occasionally on his politics – when Jock Stein asks him to give a fiver to some striking miners, for instance, or when Ferguson notices the dilapidated state of the NHS hospital which is looking after his dying mother. It’s almost as if someone in the marketing department of his publishers decided to cut out the politics. It wouldn’t sell well with the United millions, they must have reckoned, or with the airport businessmen hoping the book would give them a few tips on management techniques (which it won’t, by the way).

One would have expected far more on Fergie’s days as a young engineering union shop steward who led apprentices out on strike, and who got to know fellow union troublemakers from the Clydeside shipyards such as Jimmy Reid and Gus Macdonald. And there’s barely a word, either, on his days as deputy chairman of the Scottish PFA.

Similarly, last year’s bid by BSkyB to take over Manchester United merits just five lines and the only Murdoch mentioned in the book is Bobby. But at least Ferguson has finally made public his opposition to the Sky deal. “My own feeling,” he writes on the penultimate page, “is that this club is too important as a sporting institution, too much of a rarity, to be put up for sale.” If only he’d said as much a year ago.

Perhaps the most telling thing to emerge from his autobiography is the appalling breach in relations with Martin Edwards, which occurred long before the Sky bid. The book almost confirms reports that in recent months the two men have gone for long periods without even talking to each other. Yet four or five years ago Alex Ferguson wouldn’t hear a word said against Edwards. He felt eternally grateful for the way the United chairman had stuck by him during the dark days of 1989 and 1990, at a time when many others around Old Trafford were urging another public execution.

It all began to go wrong when Ferguson discovered that George Graham, then at Arsenal, was earning more than twice as much as he was and the United board were reluctant to rectify the disparity. It’s obvious Ferguson’s anger was fuelled further by the huge fortunes Edwards himself was earning from the growing commercialisation at Old Trafford. Yet conversely, the club’s plc status meant Edwards would not bust the club’s strict wage structure and devote smaller fortunes to buying players like Gabriel Batistuta or Ronaldo.

Although relations between the two have clearly deteriorated so badly, both parties recognise that they would each be much worse off without the other. So, far better to tough things out until Fergie retires in 2002. But if the Roy Keane saga unfolds the wrong way, and other stars are tempted to leave because United won’t pay them what they want, then one can easily see Fergie jacking it in before then.

The great irony, of course, is that it is the capitalist, free-market Thatcherite, Martin Edwards, who is insisting on the collective, egalitarian Old Trafford wage structure, while the socialist former trade union official, Alex Ferguson, is the man arguing for greater inequality in take-home pay. But then Fergie’s old union, the AEEU, always has been keen on substantial differentials.

So long as Martin Edwards stays in control at Old Trafford it’s certainly difficult to see Alex Ferguson fulfilling much of an upstairs role after he retires as manager – and he was once warned, in any case, that he’d never be allowed to stick around like Sir Matt did. If so, there’s an obvious alternative career.

The elevation to Sir Alex might have been only the first step of prime ministerial recognition. It would be just like Tony Blair, and typical, too, of Alastair Campbell, to find a job for Ferguson in the higher ranks of New Labour. Certainly in his regular bullying of journalists and his stifling of the slightest sign of dissent at Old Trafford, Sir Alex has shown himself to be on a par with the most skilled of New Labour’s spin-doctors and control-freaks.

Lord Ferguson of Govan would be the obvious solution. And who knows, he might even step into Kate Hoey’s shoes as sports minister. The government may well be looking for a good PR stunt like that, especially amid the looming political embarrassment of England failing to get the World Cup.

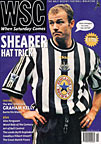

From WSC 152 October 1999. What was happening this month