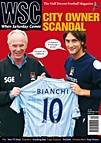

To suggest that the French midfielder has an attitude problem would be like saying Tewkesbury has been a bit damp of late. James Eastham reports on a career that has gone nowhere, via pretty much everywhere

To suggest that the French midfielder has an attitude problem would be like saying Tewkesbury has been a bit damp of late. James Eastham reports on a career that has gone nowhere, via pretty much everywhere

Stéphane Dalmat scored a glorious goal in the Champions League last season. Playing for Bordeaux, he picked up the ball on the halfway line, breezed past an opponent and lobbed PSV Eindhoven’s goalkeeper, Gomes, from 25 yards. In the Sky TV studio, Jamie Redknapp, Dalmat’s team-mate at Spurs in 2003-04, described the midfielder along the lines of being “one of the most skilful players I’ve ever seen”, but labelled his attitude “shocking”.

Dalmat was kicked out of White Hart Lane before his season-long loan had run its course, following an altercation with a youth-team player. It then emerged that he had also fallen out with caretaker coach David Pleat and several team-mates.

This was just another controversial episode in the career of the most talented French footballer of his generation. Pleat had spotted a teenaged Dalmat playing for Lens against Arsenal in the Champions League in 1998. “I immediately felt he was special. I thought there and then he would go places.” Pleat was right in one sense – Dalmat has played for ten clubs in ten years. He has failed to come close to fulfilling his potential. In June, he joined Sochaux, yet another attempt to relaunch his flagging career.

It was so different in 1999, when the 20‑year-old Dalmat moved from Lens to Marseille for 68 million francs (£7.3m), a record fee for a move between two French clubs. His effortless passing ability, two-footedness and ferocious shooting made him an almost complete midfielder. Raymond Domenech, then coaching France’s Under-21s, remarked: “At his best, he reminds me of Lothar Matthäus in his early days.”

Even before the switch to Marseille, however, the warning signs were there. After monitoring Dalmat for a season, Lens coach Daniel Leclercq commented: “At first, he seemed very nice, very straightforward. But dig a little deeper and you see he has a lot to learn about general behaviour.” Dalmat sulked for a month because Lens refused to sell him to AC Milan midway through 1998-99. “I was angry at the whole world because I was so desperate to move to Italy. I went crazy at everybody, including my team-mates and manager.”

Financial woes forced Marseille to sell him to Paris Saint-Germain for 70m francs in 2000. In the capital he sealed his enfant terrible reputation. Dalmat was part of PSG’s hugely expensive policy of buying the most exciting young French players – but he imploded. “I was 21 and had money. The Parisian nightlife is tempting. I perhaps made mistakes but was badly advised. The negative image I have comes from my time at PSG.”

Big clubs were still willing to take a risk on him. In January 2001 he joined Inter, but struggled to win a first-team place. He made just 48 Serie A appearances in two-and-a-half seasons. A couple of stupendous long-range goals reminded fans how good he was.

After Spurs he moved to Toulouse, starting brightly before a foot injury sidelined him for four months. The Ligue 1 club wanted to sign him permanently, but Dalmat refused. “I couldn’t stay at Toulouse because financially there was too great a difference between there and my final year at Inter, I’m not afraid to say it.”

There was no clamour for his signature this time, at least not from Europe’s bigger clubs. Instead Dalmat signed a five-year contract with Racing Santander, who had finished 16th in La Liga the previous season. Club president Manuel Huerta raised fans’ expectations, saying: “He will be our very own galáctico.”

Events proved otherwise. After four months of forgettable performances, Dalmat returned late from the Christmas break, provoking Huerta’s ire. “Either he changes or he will have to leave,” the president fumed. “His attitude is a problem. This ‘Monsieur’ gets up every day to collect his money while young players give everything to succeed as footballers. Dalmat has all the qualities in the world: if he applied himself, he would be a revelation in La Liga.”

Worse followed in March 2006, when the player was disciplined for failing to stop for police after driving at high speed at four o’clock in the morning. Santander terminated his five-year deal four seasons early. Dalmat reflected: “When you’ve played for big clubs in France or abroad, and you sign for Santander, psychologically you’re not as committed. I knew very well I wouldn’t spend the rest of my life at Santander. It was just an opportunity to have a good season and, why not, be sold on for a higher price.”

He signed a one-year deal with Bordeaux in summer 2006. The wonder goal against PSV aside, he made little impact. Coach Ricardo implored him to try harder in training, then dropped him. Dalmat played no part in Bordeaux’s League Cup victory or end-of-season run-in. From appearing the most likely successor to Zinedine Zidane, Dalmat is almost washed up at 28. Sochaux may be the final fresh start for a player who has often seemed to care less than those who watch him about his career.

From WSC 247 September 2007