Even once you’ve established a new pre-match routine and got on nodding terms with your seat neighbours, a real feeling of familiarity can still be years away

15 July ~ Though it seems barely credible to me, it is now over a quarter of a century since I watched my last match at Ayresome Park. Middlesbrough lost 4-2 to Derby County. In the first half Rams striker Paul Simpson so tormented Boro’s young defender Keith O’Halloran, you suspected that when the Irishman went in at the interval his shorts would be inside-out. In the second, on-loan German juggernaut Uwe Fuchs went briefly wild, scoring and thumping a few other shots narrowly wide, and the crowd celebrated his pointless act of defiance with such delirium the friend I was with raised ghosts of Mafeking Night.

Moving into Riverside Stadium the following August brought a tingle of excitement, the hope of a fresh start, a hint of dislocation and a pinch of unease, as on the first night in the bedroom of a new flat when you aren’t quite sure how much the people up above can hear.

Back then the switch to a new stadium was a novelty. Boro followed a path begun by Scunthorpe in 1988, trailing behind Walsall, Huddersfield and Millwall. Over the coming decades, however, the feelings the move evoked would be shared by fans at clubs across the country from Dorset to Wearside. Pre-match routines, passed down from generation to generation, so that not a millisecond of drinking time was wasted, lay in tatters; lucky routes that had carried clubs to glory, or at least within nodding distance of it, were chucked aside.

The Riverside Stadium was completed in such haste the club didn’t get around to providing litter bins in the toilets. When fans found there was nowhere to dispose of the paper towels they’d dried their hands on, they folded them and placed them in a neat pile next to the wash basins. It couldn’t last, of course. There is a sadness in seeing something brand new gradually losing its lustre. You want to keep things perfect. Time is the enemy. The sheen wears off, the rubs, smuts and grazes appear. The stains are psychological as well as physical. Soon you experience your debut home defeat, opening turgid 0-0 stalemate and hear – like the cuckoo announcing spring – your first cry of: “That’s it. That’s me finished. You’re not getting any more of my money, you useless shower of shithouses.”

The latter took a surprisingly long time in coming. Six months into Middlesbrough’s first season at the Riverside, a game against Wimbledon that would have had abuse rolling down the terraces like a puke green tidal wave was watched instead in pensive silence. Like newlyweds it seemed nobody wanted to be the first to break the spell and point out that, perhaps, you know, next time you might want to open the bathroom window after you’ve used the toilet.

Most animals stake out their territory using scent glands. Humans do it by squirting memories around the place. Old football stadiums are awash with the salty tang of recollection. The whiff of your past is everywhere: that is the stretch of advertising hoardings over which a legendary left-back always aimed to deposit the opposition winger with his first tackle; there is the spot beneath the floodlights where the enormous bloke in the donkey jacket lay down at half time to sleep off his pre-match lunch; over by that fence stood a man whose face was a litmus test of the home side’s performance, reddening more at every pass that went astray until on winter’s nights during a relegation season you could warm yourself on the glow of his cheeks.

It takes time, but the smell of new paint will fade, a patina will be added, but it takes years, decades. Every part of the stadium remains known solely by its official name. You feel powerless against the forces of corporatisation. Any attempt to force a likely sobriquet on something is doomed to failure. Nicknames are organic. They are not invented, they grow, and this, for the time being at least, is sterile soil.

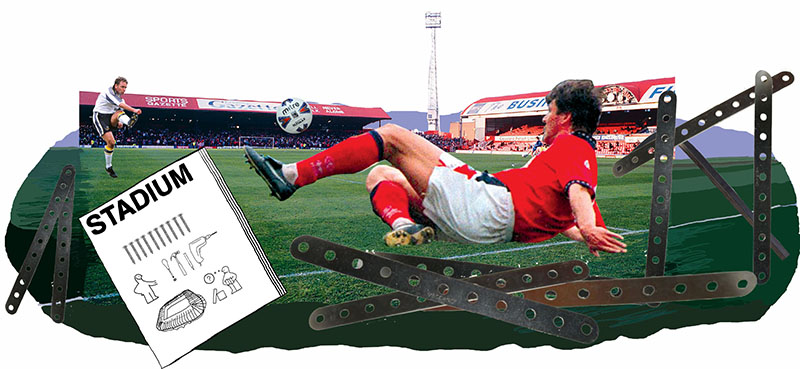

Over the years a certain uniformity among some new stadiums became apparent, as if somewhere in Britain there was a giant branch of Ikea selling flat-packed football stadiums; that on Sunday afternoons in provincial towns CEOs stood around with an Allen key in one hand and the printed instructions in another. As an away fan the new stadiums invoked a sense of déjà vu. The stands and layout often seemed more familiar to them than they did to the home supporters.

A common view these days is that football has been hijacked by the middle classes. The construction of so many new football stadiums nails that as a lie. If football really had become middle class the clubs would not have moved into brand new, purpose-built grounds, they’d have bought old ones and restored them using original fittings found in reclamation yards and French market stalls. Instead of a gleaming visitor centre with virtual reality touch screens, fans would instead be “given the tour” by the proud owners who would point at the turnstiles and say: “Those are Edwardian. Took Susie and I ages to find them. Then, one day, we got a call from a chum in Devon who’d spotted them in a field. Some local farmer was using them as part of a sheep pen, can you believe?” This would undoubtedly have been extremely irritating, especially when the phrase “our customary attention to detail” was used about “this fabulously retro 1930s gully-and-drain urinal”, but at least it would spare us the disorienting feeling of being a stranger in our own home. Harry Pearson

Illustration by Tim Bradford

This article first appeared in WSC 400, July/August 2020. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more here