An unassuming ring binder containing immaculate and comprehensive records of the first ten tournaments serves to remind us all that the joy of football is often in the detail

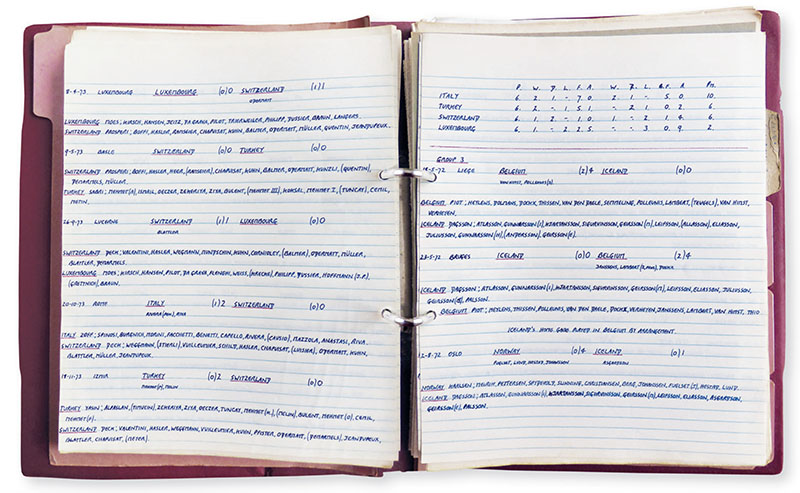

1 July ~ Soon after I started showing an interest in football, my dad allowed me a glimpse inside the maroon ring binder that would often be the focus of his attention when he returned home from the office. The cover, bearing the legend “Bank of England Exchange Control”, was unpromising, but it concealed a body of work that I found fascinating. Inside were hundreds of sheets of A4, each filled with hand-written details of football matches played long ago in and between unfamiliar countries, that together formed a complete record of the World Cup. Every game ever played in the competition, including qualifiers, was there, from the opening tie of the 1930 tournament through to the 1974 final.

Largely sourced from the classified section of World Soccer and Brian Glanville books, the wealth of information on offer was beguiling. To today’s spoilt consumer of football data, the details may seem skimpy, no possession percentages, number of successful passes or even goal times, which were viewed as something of a frippery at the time – Rothmans deemed them insufficiently relevant to record until the 1997-98 edition. Dad’s records provided everything that was important – the score, goalscorers, line-ups – and nothing else.

Their attractiveness was part of the charm. In all other known examples, Dad’s handwriting is shocking, but here the information is presented immaculately, in fountain pen and with consistent, sloping capitals, evidence of the care taken in producing it. There are pleasing individual touches – the use of larger numbers for full-time scores than for half-times; the references to “London” rather than “Wembley” as the venue of games played at England’s national stadium; the full stops after the digits in the tables. In demonstrating that the presentation of a football result can have a distinctive and aesthetic quality, he gave me a passion for capturing statistics that has endured.

Indeed, I realise it is the record-keeping, rather than the sport itself, that has driven my appreciation of football. As a fan, the joy of victory is heightened by the prospect of committing details of the success to paper; the disappointment of defeat alleviated by the knowledge that there are at least events to note, numbers to adjust. As a player, I was always eager to take a penalty, aware that the anticipation of writing “(PEN.)” after my name – with a full stop to indicate the abbreviation, as was my dad’s style – would make up for the embarrassment of seeing my scuffed effort trundle past a goalkeeper wrong-footed by a misguided expectation of power and placement.

But my records lacked the ambition and comprehensiveness of Dad’s. He had compiled a consolidated repository of information that had no comparison. Back then, if the result of a qualifier from Eastern Europe made it into the press – an unlikely scenario given print deadlines and minimal interest in foreign football – it would disappear with the newspaper, re-emerge briefly in the latter pages of the following season’s yearbooks. Only in Dad’s work would its context be clear and its permanence assured.

It was always my dad’s intention to keep his records up-to-date, but they conclude at the end of that “Tenth Tournament”, as he headlines it, in West Germany, untouched for 30 years or more. Spare time became harder to find as he tried to make a living and, as he fell behind and the tournament kept expanding, the task required to update the records became too daunting to contemplate.

I imagined taking them on and completing them, relishing the opportunity to work on a project so much more worthy than any of my own. But it has seemed less vital to do so as time has gone by and the accessibility of exhaustive data has eroded their uniqueness. Recording the results now would feel like a duplication of effort imbued with a sense of futility that Dad wouldn’t have felt.

And yet, as a historical record, Dad’s work still stands up. It will give you more detail on a qualifier for the 1962 tournament, for example, than can be found on FIFA’s own website. While the latter will tell me that Sweden beat Belgium 2-0 in October 1960, I need to refer to the folder to discover who played and who scored the goals. There are countless such examples, enough to confirm that the yellowing pages within Dad’s file remain a relevant, beautiful labour of love and that I should do my bit to ensure that they are not forever stuck in Munich in 1974. Csaba Abrahall

This article first appeared in WSC 388, July 2019. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more here