DeCoubertin Books, £20

Reviewed by Dan Davies

From WSC 383, February 2019

Buy the book

In one of his final acts as Manchester United manager, José Mourinho chose to pay tribute not to one of his own players, but to Liverpool’s Andy Robertson. “I am still tired just to look at Robertson,” he said of the rampaging Scottish left-back after his team had been dismantled 3-1 at Anfield. “He makes a 100-metre sprint per minute! Absolutely incredible.”

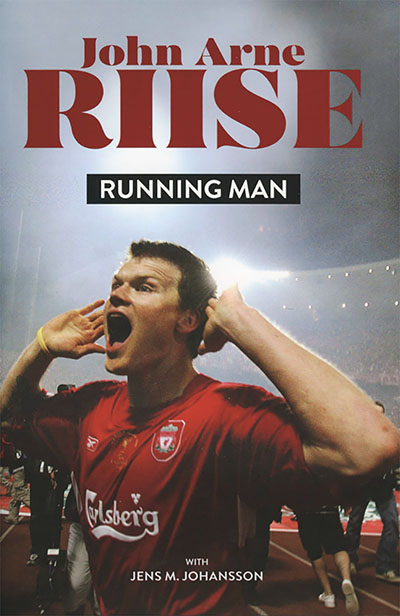

It’s something of a neat symmetry then that the autobiography of one of Robertson’s predecessors, John Arne Riise, should be titled Running Man. The Norwegian also became something of a cult figure, chiefly thanks to a series of pile-driving early goals delivered with his sledgehammer of a left foot, and through the Kop’s subsequent appropriation of DJ Otzi’s track Hey Baby to serenade him.

Riise went on play for Liverpool 339 times over the course of seven years, and he writes insightfully about the circumstances that saw him picking up League Cup, Champions League and FA Cup winner’s medals along the way. He also became Norway’s most-capped player, not that he ever felt appreciated back home.

These achievements perhaps become more notable when set against the backdrop to his professional career. The prologue to the book, which was written in collaboration with Jens M Johansson, an award-winning journalist and author, is a conversation between the two men. It quickly becomes evident that Johansson is adept at getting the player, who also had spells with Monaco, Roma and Fulham, to discuss uncomfortable issues. It’s also clear that Riise is grappling with demons that are all-too familiar to him.

These demons are laid bare throughout the book. In the earliest chapters he admits that he “wasn’t liked as a child” before describing growing up in Norway, his parents’ ugly divorce, living in relative poverty, the bullying he suffered at school, and the loneliness and self-doubt these produced. These formative experiences created a void that the young Riise attempted to fill with an obsessive approach to running long distances, honing his skills, and, later, proving the doubters wrong. This unswerving focus on himself would serve him well as a player but less so as a son, a husband and a father.

Later in the book, he talks in more depth about his complicated relationship with his mother, who, it transpires, shares her son’s less than glowing reputation in Norway. It is a reputation he feels is unfair given his success but one that he is also self-aware enough to acknowledge his part in through his desperate desire for recognition, and a too frequent propensity for embarrassing himself.

In covering the glories of Istanbul in 2005 and Cardiff in 2006, the vicious bust-up with Craig Bellamy in a Barcelona hotel, and the experience of playing at Fulham under Felix Magath (a manager who once recommended a German cheese spread to treat a thigh injury), Riise ticks all the boxes for a decent football autobiography. But it is his readiness to confront the most painful, humiliating and uncomfortable aspects of his past – and of his personality – that elevate the book. One senses that Johansson had a big part to play in this.