Simon and Schuster, £20

Reviewed by Huw Richards

From WSC 363, May 2017

Buy the book

Was Brazilian football ever more impossibly cool than when it was incarnated at the 1982 World Cup by Sócrates? It would have been enough that he was a gloriously freewheeling playmaker with a loose-limbed gait capable of works of art like his goal in the pool match against the Soviet Union. But he was also a qualified doctor, a pro-democracy activist amid Brazil’s nervous navigation away from military dictatorship, and there was his name – not a nickname, but one bestowed at birth by a father with a taste for Greek philosophy.

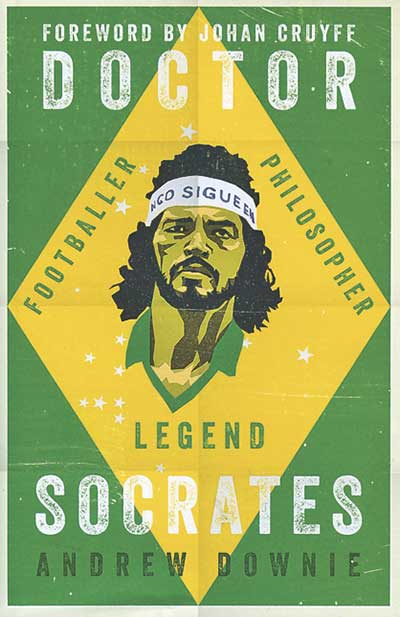

Such a phenomenon deserves the rounded, accomplished biography he has been accorded by Reuters writer Andrew Downie, who draws on a knowledge not merely of Brazil’s football but of its wider politics and society based on 17 years living there.

Downie celebrates the brilliance and the achievements. He shows how Sócrates’ naive initial

acceptance of Brazil’s political status quo evolved into a sophisticated and influential critique, at the same time as a young man who regarded football as a fun diversion from his real business in medicine became one of the world’s best and most exciting players.

But he is never carried away by his admiration. He suggests that Sócrates’ loathing of the football authoritarianism had far more to do with resentment of the way it limited his carousing rather than any more selfless motive. And, in an intriguing examination of the “Corinthians Democracy” experiment at Sócrates’ club, Downie shows how he both undermined the basic principle and sabotaged the practice by conniving with other players to import the divisive goalkeeper Émerson Leão.

Most of all he shows the extent to which Sócrates’ charisma – he was a spectacular womaniser long before he found fame – and on-field brilliance led to indulgence for his serial shagging and Olympic-standard drinking.

It is a chronicle of self-indulgent arseholery which leads Downie, in the footsteps of many others, to lose patience with his subject and issue a forceful denunciation: “One of the consequences of living for the moment is that other people’s moments do not matter. Sócrates did what he wanted when he wanted and the people around him were expected to join in or suffer in silence. And the older he got, the less time he had for moderation or restraint.”

This is, in the sense that his namesake and other ancient Greeks would have understood, a tragedy – the story of a man of supreme accomplishment brought down by failings of character, in his case to the extent of drinking himself to death at 57. It is also a familiar sporting trajectory. But the sense of loss and waste in his case is that much greater, in part because of what football means to Brazil but more for what he might have accomplished for his country in medicine, politics or both had his immense gifts been wedded to a modicum of self-discipline. A terrible tale, extremely well told.