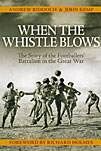

The Story of the Footballers' Battalion in the Great War

The Story of the Footballers' Battalion in the Great War

by Andrew Riddoch & John Kemp

Haynes, £19.99

Reviewed by Harry Pearson

From WSC 267 May 2009

Football folk are fond of commenting that some event – a natural disaster, terrorist outrage, loss of a relative to disease – has “put things in perspective”. And you can almost guarantee that five minutes later they’ll once again be arguing about a penalty decision as if their life depended on it.

Andrew Riddoch and John Kemp’s lucidly written and extraordinarily well-researched book tells the story of 17th Battalion the Middlesex Regiment. Named “the Footballers’ Battalion” because most of its soldiers were recruited from amateur and professional clubs, the 17th was raised in 1914 – a time when there was mounting pressure on professional clubs in particular to “do their bit” for the war effort – and went on to fight at the Somme (where 500 of its officers and men were killed in less than three weeks), Redan Ridge (300 more dead) and Oppy (462 fatalities). You’d be hard pressed to find anything more likely to put things in perspective than this.

Though When The Whistle Blows is more a work of military history than a piece of sports writing, the game underpins the story throughout and the nuggety details of the men’s pre-War careers adds poignancy – if any more were needed – to a colossal story of hardship and struggle broken by the occasional game for the regimental XI.

Among the lost were Sid Wheelhouse, captain of Grimsby Town and “a model player both on and off the field who endeared himself to all who knew him”, Bob “Pom Pom” Whiting, the Brighton and Hove Albion goalkeeper “renowned for the phenomenal distance of his goal kicks”, and John “Ginger” Williams of Millwall and Wales who rode “a bamboo bike as part of his fitness regime”.

The fortunes of those members of the battalion who survived the Western Front were mixed. Major Frank Buckley had a long career in management, notably at Wolves where he earned notoriety for his involvement with “monkey glands”; Jack Cock was transferred from Huddersfield to Chelsea in 1918 for a fee of £2,650 and went on to appear in feature films; Fred Keenor shook off the effects of a wound in the knee and lead Cardiff to FA Cup victory in 1927, while Fred Bartholomew of Reading became the groundsman at Elm Park, retiring in 1957. Others fared less well. Bristol Rovers goalkeeper Peter Roney suffered what would now be call post-traumatic stress and died a broken man; Tommy Barber played a few games for Crystal Palace and Walsall and then succumbed to tuberculosis; Joseph Mercer of Nottingham Forest was wounded and captured and never recovered his health, dying a few years after the Armistice. His son Joe would have the playing and managerial career denied him.

And then there was Captain Allastair McReady-Diarmid, awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his part in stopping the German counterattack at Cambrai in 1917. Armed with a revolver and bag of hand grenades he is reported to have killed or wounded 94 enemy soldiers before he himself died in a bomb blast. Next time some pundit slumped on the TV studio sofa talks idly of a midfielder being “the type you’d want with you in the trenches” I think we might all spare a small thought for the captain.