Search: 'Benfica'

Stories

The cups presented for many modern competitions often lack the appeal of their predecessors

Via The Set Pieces

11 August ~ Last season Wolves supporters were stuck in a state of apathy. Then over summer Fosun, a Chinese investment group, efficiently and professionally completed their takeover, transforming the mood among the fanbase.

Vulgar commercialism aside, the European Cup’s lustre is built on a monopoly

1 June ~ Liverpool v Milan in 2005 then 2007; Manchester United v Barcelona in 2009 and 2011; then, on Saturday, Real Madrid defeated Atlético Madrid in the Champions League final for the second time in three years. UEFA competition has become a boring fait accompli, yet I still love the European Cup final. A marathon of cynical commercial tat, including some of the preening participants, it remains the most genuinely heavyweight fixture in club football – and an unmissable date with the television.

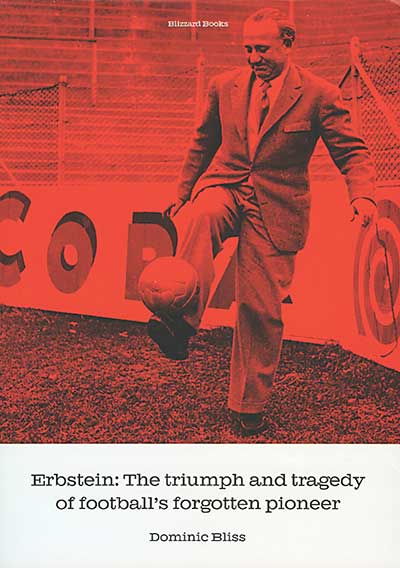

The triumph and tragedy of football’s forgotten pioneer

The triumph and tragedy of football’s forgotten pioneer

by Dominic Bliss

Blizzard Books, £10

Reviewed by Jonathan O’Brien

From WSC 340 June 2015

Erno Erbstein is a deeply niche subject for a book, the first to be published by Jonathan Wilson’s quarterly which has won a deserved reputation for quality output over the last few years. Though the incident in which Erbstein perished – the 1949 Superga air disaster that wiped out the entire Torino squad – is one of the defining moments of Italian football history, his own story has slipped through the cracks of memory until now. And though he came from the same central European Jewish coaching lineage as Hugo Meisl and Bela Guttmann, he’s far less well known than either of them (as the title of this book implies).

Five years in the writing, Dominic Bliss’s biography is a hugely well-researched and elegantly written study of a man whose life was punctuated with innumerable dangers and hardships (he served briefly in the First World War and later survived the Holocaust). Perhaps unsurprisingly in view of this, as a player Erbstein gained a reputation for a robust style: a particularly poor challenge on an opponent during a match was one of the two reasons he got out of Budapest in the 1920s. The other was the dark shadow of encroaching anti-Semitism.

In 1928, Erbstein began coaching in Italy, where he assembled a series of tightly organised teams from seemingly unpromising materials, like a proto-Otto Rehhagel. He put the emphasis on quick-fire passing and subjected his players to relentless drills, so that they would be able to pass to each other in their sleep. And the results, initially unspectacular, soon flowed easily: he got the tiny Lucchese club up to a seventh-place finish in Serie A, for example. “He conceived a mode of football 30 years ahead of its time,” says one Sardinian journalist whose father was in the Cagliari youth team while Erbstein was manager there.

Sadly, like so many other Jews, Erbstein spent all too much of his life frantically moving around Europe in search of sanctuary. Benito Mussolini’s 1938 Manifesto of Race forced him to flee again, this time back to Hungary, where he went into business with his brother. He narrowly saved his wife and daughters from death at the hands of the Nazis by utilising one of his innumerable connections (a story recounted in gripping detail here by his daughter Susanna, who’s now in her 80s). Meanwhile, he himself, along with future Benfica manager Guttmann, jumped off a train taking them to a concentration camp in Germany.

After the war, Erbstein came back to Torino, where he had been coaching before Mussolini’s reign of terror. They had won the league twice in his eight-year absence, but now he and club president Ferruccio Novo made them an even better team who cruised to two more championships. Had the European Cup existed at the time, they would undoubtedly have won it at least once. And then, on May 4, 1949, came Superga. This is a sad book in many ways, unashamedly esoteric, and also a fine one.

The approved biography of George Best

The approved biography of George Best

by Duncan Hamilton

Century, £20.00

Reviewed by Robbie Meredith

From WSC 322 December 2013

Despite what Immortal would have you believe, George Best divides opinion in his home country. For each of the tens of thousands who stood reverently in the Belfast rain for his 2005 funeral, there is a counterpart embarrassed and infuriated by the constant scandals and drunken antics. It is a mark of his status, of course, that most people in Northern Ireland still care enough to have an opinion about Best – good or bad – and it is unlikely that Duncan Hamilton’s “approved” biography will change what they think. Written with the blessing of Best’s sister Barbara, the sibling most active in guarding his memory, Immortal has few words of condemnation for even the worst of his excesses, preferring to depict chaos engulfing Best, rather than something he was primarily responsible for.

The early chapters, detailing his rise, are familiar but still thrilling. The shy, good-looking boy from Belfast, spotted by the legendary scout Bob Bishop and a surrogate son to Matt Busby, becomes the fulcrum of an outstanding Manchester United team until Europe is conquered when Best is barely 22. Even in the “el Beatle” years, he lodged in a neat terraced house with the redoubtable Mary Fullaway, and it was a home he would often return to even as things were going wrong in later years.

Yet the hour of Best’s greatest triumph, that 4-1 victory over Benfica at Wembley, is the beginning of a long, drawn-out end. Despite his iconic goal he felt he hadn’t played well in the final, a portent of disappointments to come. In the troubled aftermath the book, echoing its subject, rather loses its way. While we now know much more of the twin afflictions of alcoholism and depression, from which he undoubtedly suffered, I suspect that Hamilton makes more excuses for Best’s behaviour than Best, to his credit, actually did.

For, as Hamilton tells it, Best suffered primarily from feeling an excess of love, not for the booze and birds of tabloid tales, but for football and primarily Manchester United. His life does indeed come to resemble a kind of hell – in one telling passage, coachloads of visitors come to picnic in the unfenced garden of his ill-advised modernist home, Che Sera, and turn it into a spectral prison by gawping constantly through the all-encompassing glass.

Immortal becomes a long plea for understanding, and a lament that it wasn’t a quality successive Manchester United managers after Busby displayed in Best’s case. Yet although he was in the grip of twin evils, it is hard to see how Wilf McGuinness or Frank O’Farrell could have made more allowances for him, and Hamilton protests too much when he dismisses Best’s drink-driving, assaults and violence against women in little more than a few sentences.

Hamilton is a terrific writer but he seems more determined to be sympathetic towards his subject than Best, in his more reflective moments, was about himself. Immortal is a fine biography and a fascinating portrait of a dawning age of sporting celebrity, but will appeal most to those already inclined to view Best as the last of the doomed football romantics.