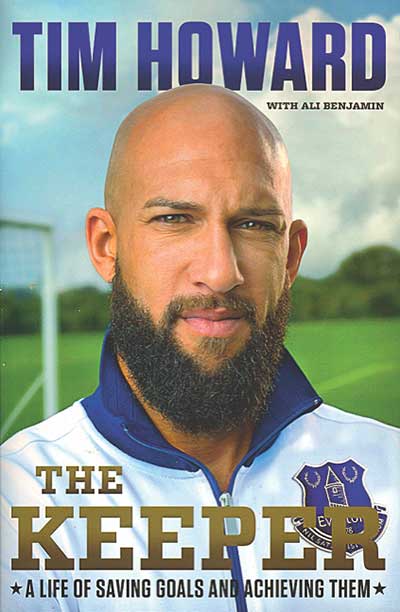

A life of saving goals and achieving them

A life of saving goals and achieving them

by Tim Howard with Ali Benjamin

Harper Collins, £18

Reviewed by Ian Plenderleith

From WSC 338 April 2015

Twice in two pages I laughed out loud during this otherwise unfunny book. When a young Tim Howard arrives in England to play for Manchester United, he calls his compatriot Kasey Keller in London for some advice. “Well, Tim,” says the older, wiser sage of White Hart Lane, “I guess my advice to you would be this: make as many saves as you can.”

Just seven paragraphs later, Howard recalls his senior debut for United and captain Roy Keane’s pep talk before the 2003 Community Shield game against Arsenal. “Just pass it to a red shirt, guys. It’s as simple as that: take the ball and pass it to another player in red.”

The problem with reading footballers’ autobiographies is that you rarely learn anything new. Not about the game and not about the player. As David Foster Wallace wrote in his review of tennis star Tracy Austin’s life story, such books are “at once so seductive and so disappointing for us readers”, because the player is only equipped to “act out the gift of athletic genius”. If they were able to articulate that gift, they probably wouldn’t possess it

at all.

That’s where the ghost writer comes in, but they can only work with what they’re given. Howard’s flat account of his life is imbued with the kind of sentimental journalese that signifies a second pair of hands. His ability to overcome Tourette’s syndrome is interesting and admirable, but is not compellingly told because the writer fails to get inside Howard’s head. Either the goalkeeper wouldn’t let her in, or she chose not to go there. While there may have been good reasons for that, it fails to lift the book above its absolutely ordinary level. Instead, the tension is stressed on the Belgium v US World Cup round of 16 game in Brazil, with interludes between each chapter taking us through the action. This was of course a heroic performance by Howard, but we know how it ended. The US lost. It was just last summer, remember?

In fact the most intriguing thing about Howard’s book is how he dodges the issue of his failed marriage. For the longest time we hear only wonderful things about his wife, Laura. Then while in South Africa at the 2010 World Cup Howard blithely springs it on us that he doesn’t miss her any more. He blames the “suspended reality” of life as a football player, “where we retreated… into a kind of grade [junior] school mentality”. His previously extolled faith in God is suddenly of no help. Being “addicted to my job” is the closest we come to learning why he gets divorced from the seemingly perfect mother of his two children (I really hope Laura got a better explanation than that).

Such withheld integrity makes this kind of book a bust. It exists to sell, not because Tim Howard wants to share his world with you. If there’s no narrative, you should stick to making as many saves as you can.

My autobiography

My autobiography My autobiography

My autobiography A football life

A football life