Search: 'Alex James'

Stories

Leicester 17th, Chelsea champions and Watford relegation – what WSC contributors got right and wrong about the previous season

12 August ~ “The arrival of manager Claudio Ranieri doesn’t seem to be the most reassuring,” wrote Leicester City fan Simon Tyers in WSC’s 2015-16 season guide last summer. “I’m still confident we’ll survive… but probably with someone else at the helm.” He wasn’t alone, with the Foxes averaging 17th position among the rest of the Premier League contributors’ forecasts.

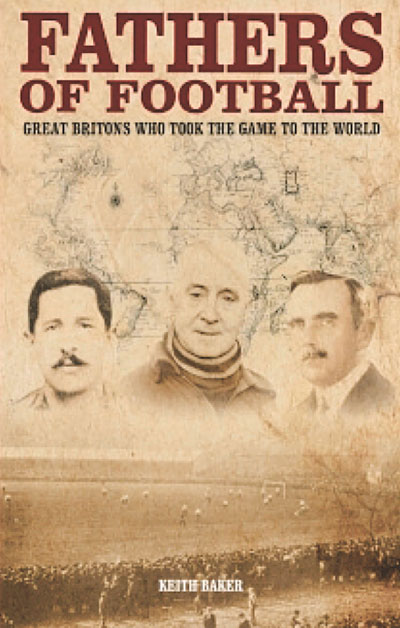

Great Britons who took the game to the world

Great Britons who took the game to the world

by Keith Baker

Pitch Publishing, £12.99

Reviewed by Paul Brown

From WSC 341 July 2015

Britain did not invent football, as Sepp Blatter would no doubt remind us, but it did knock it into shape, drawing up rules, forming clubs, organising competitions and sending the association version out into the world. British migrants, travelling with Laws of the Game pamphlets and deflated leather casers in their suitcases, became football missionaries, teaching and inspiring new converts, and sowing the seeds for what would become an international obsession.

In Fathers Of Football, Keith Baker profiles several of these pioneers of the world game, many of whom remain relatively unknown in their home country. Take James Spensley, who left Britain in 1896 to work for an insurance company in Genoa. Today, Spensley has an Italian park, street and junior football tournament named in his honour. His great contribution to football in Italy began when he persuaded the expat Genoa Cricket and Athletic Club to take up the association game (and to admit non-British members).

Spensley became the club’s goalkeeper, captain and de facto manager, leading Genoa to six Italian championships between 1898 and 1904. Their success saw the club renamed the Genoa Cricket and Football Club – a name they retain today. The influence of British pioneers can be seen in the Anglicised names of several international football clubs: Genoa rather than Genova; Milan rather than Milano; Athletic rather than Atlético.

Some of the individuals profiled here may already be familiar to football readers. Charles Miller is popularly regarded as the father of football in Brazil, and was the subject of various colour pieces during last summer’s World Cup. Alexander Hutton is similarly regarded in Argentina. Meanwhile Jimmy Hogan’s incredibly influential contribution to the development of football in Austria and Hungary (via the Netherlands, Switzerland, France and Germany) is well documented, although it remains a remarkable story.

More obscure are the Charnock brothers, Clement and Harry, who do not have so much as a Wikipedia entry between them, despite the role they played in the development of football in Russia. The brothers, from Lancashire, travelled to Moscow around 1890 to manage textile factories. Both men encouraged their employees to take up football and inspired the formation of several clubs, despite state opposition to organised activities involving workers. Harry’s OKS (Orekhovo Sports Club) were a founding member of the Moscow League, and won five consecutive championships between 1910 and 1914, playing in front of crowds of around 15,000. However, after the Revolution in 1917, OKS were placed under the control of the Cheka – a forerunner of the KGB. The club were renamed Dynamo Moscow, and the Charnocks were expunged from their history. They deserve to be better remembered.

Baker makes it clear that his “Great Britons” were not solely responsible for the spread of association football around the world, and he places the growth of the game into wider historical and social context. But his concise and informative book pays tribute to their individual achievements, and provides an illuminating record of their contributions to the world game.

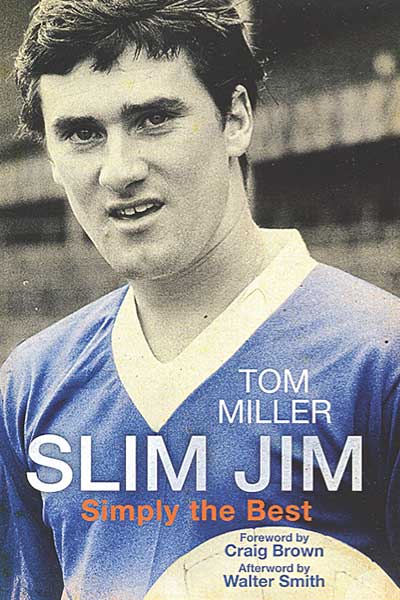

Simply the best

Simply the best

by Tom Miller

Black & White, £9.99

Reviewed by Gordon Cairns

From WSC 337 March 2015

The radio football parody Only An Excuse captured the Scottish perception of Jim Baxter almost to perfection back in the 1980s. His character explains his most famous performance, against England in 1967 where at one point he juggled with the ball: “I had a couple of great teachers… and three White & Mackays and a double Grouse, before I went on the pitch, like. That would explain the languid fluidity.” Unfortunately, the only inaccuracy was the choice of spirit – Baxter preferred Bacardi over whisky. Tom Miller tries to expand on the popular caricature of an incredible footballer who loved a drink by offering an explanation for Baxter’s self-destruction in this new biography, with somewhat limited results.

James Curran Baxter is often described as Scotland’s greatest player but ended a 12-year playing career with only ten domestic medals, which was not a lot given that Rangers were the dominant team in Scotland for most of his time at Ibrox. Perhaps that is why his eulogists focus on individual performances, including two victories at Wembley and being picked for a Rest of the World select. However the extent of Baxter’s drinking and lack of training must surely limit claims that he was truly world class. Although alcohol abuse was rife in the football culture of the 1960s, it’s questionable whether you can consistently operate at the top level with high volumes of alcohol in your bloodstream – Pelé and Eusébio weren’t playing with hangovers.

It seems Baxter’s problem was that he simply didn’t value the natural ability that raised him out of the ordinary, his career a long attempt at sabotaging the skill he possessed. In the most interesting chapter, sports psychologist Tom Lucas examines how never being acknowledged by his birth parents as their son during his playing career may have affected Baxter. (He grew up thinking his real mother was his aunt, who he was raised by.) Lucas’s conjecture is that the pitch was the only place Baxter could escape from the pain of rejection by his mother while his womanising could be connected to his feelings of abandonment.

Published two years after what was billed as “the definitive biography”, the bulk of this book rehashes the well-worn tales of Baxter’s drinking, gambling and occasional footballing. Miller, an in-house commentator for Rangers, didn’t have to wander far in his choice of interviewees, the majority of whom seem to come from the club’s “family”, including current defender Darren McGregor and youth-team coach Davie Kirkwood, I assume because both had played for Fife clubs like Baxter, hardly justifying their inclusion. Baxter’s own voice is barely heard, yet for most of his playing career he wrote syndicated columns. Although ghost-written, surely a trawl through these would have unearthed something more relevant than how McGregor felt when he joined Rangers.

The inclusion of two poems and a selection of pen portraits from the back of football cards feel like fillers to make the book up to the required length. There is no interview with Alex Ferguson, who played alongside Baxter; Scotland’s greatest manager’s views on getting the best from Scotland’s most talented player would have been compelling. Neither is there any input from Baxter’s sons or first wife, which could have given greater insight into how he felt about family, especially if he had issues about abandonment.

My life in football

My life in football

by Howard Kendall

De Coubertin Books, £20

Reviewed by Simon Hart

From WSC 323 January 2014

There is a lovely anecdote in Howard Kendall’s new autobiography about the day he signed Dave Watson for Everton from Norwich City. It was two days before the start of the 1986-87 season and Kendall’s attempt to complete the deal by five o’clock, so ensuring Watson’s availability for the opening fixture, had failed. Undeterred, he had the clock on the wall turned back an hour and got Watson to pose for a photo beneath it. “The Football League accepted it and Dave made his debut,” he writes.

Timing is a recurring theme in this recounting of Kendall’s career. He was ahead of his time as both a player and manager. He became the youngest player in an FA Cup final when, at 17 years and 345 days, he appeared for Preston against West Ham in 1964. At 20 he was wanted by Bill Shankly but joined Everton instead. He entered management with Blackburn at 33, winning promotion immediately. With Everton, he won the League, FA Cup and European Cup-Winners Cup before his 39th birthday.

So much so young, yet Kendall’s timing was out in one crucial respect: the post-Heysel ban denied Everton European Cup football and he cites this as the reason he left for Athletic Bilbao in 1987 (as a 45-year-old Alex Ferguson was still settling in at Old Trafford). Familiar stuff but what is new here is the revelation that an unnamed “Liverpool executive” had recommended him to Athletic after blocking their move for Kenny Dalglish – a “grim irony” indeed for Evertonians.

Written with James Corbett, who collaborated on Neville Southall’s autobiography, Love Affairs & Marriage: My Life in Football is very much what the second part of the title tells us. As befits an old-school gentleman, Kendall barely mentions his private life and dwells only briefly on potential controversies such as his departure from Notts County amid “ridiculous allegations” (unspecified here but drink-related). Yet there is much to enjoy nonetheless, not least the account of how he assembled his great Everton side in an era when a manager could create something special with a combination of homegrown talents, astute transfer dealings (he recalls the gambles taken on the injury-prone Peter Reid and Andy Gray), a trusting chairman – and morale-building Chinese dinners.

Kendall, with his man-management skills and love of the training pitch, differed so much from his own Everton boss Harry Catterick – from whom, he notes, he learned just one football lesson in six and a half years – yet the big question mark of his career is why after so much early success, his only subsequent trophy was an Anglo-Italian Cup with Notts County in 1995. Kendall reflects on his two less happy spells at Goodison in the 1990s, noting the lack of boardroom support and arguing that the influx of big money into the game meant it was no longer possible to build success on a budget. “Players were harder to sign,” laments the man whose first Everton buy, Southall, was recommended by a friend who ran a Llandudno pub. The end result is he was effectively finished as a manager at just 52 – a man out of time once more.