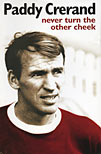

Never turn the other cheek

Never turn the other cheek

by Pat Crerand

Harper Sport, £18.99

Reviewed by Ashley Shaw

From WSC 254 April 2008

You would struggle to find a more optimistic Manchester United pundit than Patrick Crerand. Ever bullish about the club’s prospects and reluctant to criticise the team’s poorest displays, he makes an enthusiastic cheerleader and the perfect summariser for MUTV. The title of his autobiography portrays the subject as an uncompromising Scot unafraid of settling an argument with his fists. Yet throughout it throws up surprises. During an appearance on the Kop to take in a Liverpool match in the 1960s, he and some fellow United players suffer Scouse witticisms but no worse, “a contrast with today’s Liverpool supporter”, he suggests.

Crerand pops up again at a safe house in Derry at the height of the Troubles to talk to the IRA – although he admits that the terrorists just want to discuss football and largely ignore his political pleas. Nevertheless, Never turn the other cheek is no-run-of-the-mill autobiography – how could it be with connections like that?

Coached by Jock Stein in the Celtic youth team, Crerand’s rise to the first team brought only disillusionment, culminating in a half-time bust-up with manager Sean Fallon during an Old Firm game on New Year’s Day 1963. Celtic fans were shocked when the rising star subsequently left for United, playing a blinder in that year’s FA Cup final to secure the club’s first success since Munich.

During his United career Crerand was regarded as Busby’s representative on the pitch – a player built in the boss’s image (a stylish wing-half renowned for shrewdness rather than pace and power) – while off it the pair were close enough for Crerand to play go-between in the audacious attempt to recruit Stein in 1971 and other backstairs deals.

Crerand largely denies his presumed role in the decline at the club in the six years following the European Cup triumph in 1968. It has been widely assumed that his closeness to “the boss” undermined Busby’s immediate successors. Instead he blames the tactics of Wilf McGuinness and Frank O’Farrell and the new-fangled training regimes belatedly introduced to the club by the pair and the poor players recruited in this period.

After his playing career, Crerand was promoted to assistant manager alongside Tommy Docherty, whom he had helped bring in from the Scotland job. Yet the pair shared little in common and, sure enough, the relationship declined into mutual hatred. Nevertheless they contributed to a fantastic revival, turning a club struggling for goals in 1974 into the most exciting in English football by 1975.

Crerand’s list of grievances against Docherty could run to a book by itself, but the latter’s approach to man-management was summed up by the “disgraceful” treatment of Denis Law and the manner in which the old guard were pensioned off. After trying and failing at club management at Northampton, Crerard quit the game to become an after-dinner speaker, salesman and publican before moving to MUTV in the 1990s.

NTTOC is only marred by what is omitted. For a man who professes to be a staunch socialist and is rightly regarded as the keeper of the Busby flame, there is no mention of the Glazer takeover, save a grumble about ticket prices. It’s unfortunate that Crerand should avoid this issue as his honest views about the American owners’ debt-laden plans for the club would make interesting and entertaining reading. Perhaps Crerand, like another Scot at the club, wisely prefers the diplomatic approach to his paymasters. That aside, this is a cut above the usual fare.