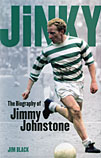

The Biography of Jimmy Johnstone

The Biography of Jimmy Johnstone

by Jim Black

Sphere, £18.99

Reviewed by Graham McColl

From WSC 247 September 2007

The post-football fate of Jimmy Johnstone is one of the best arguments that can be mustered in favour of the super-inflated salaries of today’s footballers. He was voted the greatest ever Celtic player in 2002, yet for the previous two decades, after finishing with football as a player, he had found himself skint and, as outlined here, spent that period meandering unsatisfyingly through various menial jobs. These included three years as a manual labourer and, irony of ironies, a spell as a satellite-dish salesman, purveying the very piece of equipment that has made today’s players rich beyond Jimmy’s wildest dreams.

It was tragic to see Jimmy ravaged physically by motor neurone disease in the final five years of a life characterised by his being a ball of perpetual motion on and off the football field. His death in 2006, aged only 61, concluded the story of “the Scottish George Best” as Giacinto Facchetti, the great Internazionale defender, described him, but in his final years Jimmy was indifferent to the idea of relating that enormously eventful life story in an autobiography. It is with some apprehension, then, that one opens the pages of this biography, rushed out just a year after his passing.

Puzzlingly, no members of Jimmy Johnstone’s family appear to have been interviewed – surely vital for a book such as this? The author presents a picture of an often maddening, seriously troubled, shy individual, but inside information from those who knew him best might have clarified aspects of Jimmy’s character and motivations quite properly hidden from the public during his lifetime. There is no sustained attempt to delve deeply into his personality, which was surely related closely to his individualistic style as a player. Instead, we get this bland explanation for a complex, brooding, often explosive personality: “Perhaps it had something to do with being a redhead, for most associate red hair with a quick temper.”

Often, Jimmy is threaded into the tale only here and there and frequently he is absent from his own story altogether, when you might expect him to be entirely to the fore in his own biography. Too frequently, non-sequiturs and irrelevancies jostle dully for attention and hoary old facts, trotted out to fill up the pages, trip up and waylay the flow of the story.

There are occasional enlivening mom-ents, such as a suggestion that Johnstone’s international career was stunted by him plundering a couple of bottles of champagne from the room of Tommy Docherty, then Scotland manager; and, perhaps worse in Docherty’s eyes, replacing them, when caught, with a greatly inferior brand.

The conclusion of the story, with the details of a five-year battle against motor neurone disease, is genuinely moving; painful to read, too. Overall, though, readers are likely to experience a familiar feeling to that experienced by inferior opponents when confronted by Johnstone in his heyday; just as you seem to be getting close to getting to grips with Jinky, he slips frustratingly away.