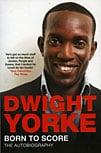

The Autobiography

The Autobiography

by Dwight Yorke

Pan Books, £7.99

Reviewed by Damon Green

From WSC 280 June 2010

Tits. He's seen a few. Especially in the latter days of his career. Graeme Souness tried – he says – to break his leg during a five-a-side game. Roy Keane has the management skills of a psychopathic Mr Bean. And Peter Andre has no idea how close he came to being strangled to death.

But I nearly didn't get that far. Twice I was tempted to leave Born To Score on the bus: firstly when it took seven pages to describe the banal details of his transfer to Man Utd (the 1996 League Cup final – one of his finest performances in a Villa shirt – gets 12 lines); secondly when the author devoted five pages to his first meeting with Katie Price (they went to McDonald's. He had Chicken McNuggets. She paid).

Not that the good stuff isn't there, if you know where to look. On his metamorphosis from bit-part wideman to one of the finest strikers of a generation, we get the moment where Brian Little invests his total confidence in Yorke and the player's subsequent realisation, as he "rag dolls" Colin Hendry, that his skills can dominate his most feared opponent. Doug Ellis was prepared to chuck money at him to keep him – a bigger salary than United were offering and a million-pound signing-on fee – which may surprise critics of Doug's stinginess. Stan Collymore really did think he was The Man, but was the only one who did. Yorke's still bitter that Graham Taylor never took him back at the end. Ugo Ehiogu smokes like a chimney.

But the problem with this book is that there are three different stories here: the one that I want to read, the one that the author wants to write and the one that Dwight Yorke is actually trying to tell. You know what ghost-writer Martin Swain thinks the story is: That Night In Barcelona, all this stuff about "scoring". But at times you can hear the leading questions echoing back from Yorke's baffled unreflectiveness. Discussing the fabled Yorke/Cole partnership, for example: "Did we talk about it? Plan things? Work things out? No, not really. It just, well, happened. I wasn't even that aware of it." And when discussing the fleshy side of his trophy-hunting, we often get a woodenness that's pure Cholmondley-Warner: "On one such occasion, I recall leaving with a girl whose name – try as I may – I cannot remember but with whom I ended up enjoying a night at my house." Cor.

Supporters make the best football historians, not because our memories are particularly reliable, but at least the games mean something to us and the meaning turns them into stories. Dwight plainly has no recollection of any match he ever played. Not the trial game that got him noticed by the Villa, not his first league appearance. It's only at the end that you find the story that Dwight himself is trying to tell and it's not about football. It's a story we've all heard in other places – over a drink after work, during a fag-break by the fire escape – it's the story of an unrequited dad. Bitterly upset at his estrangement from his son Harvey, and the perceived attempts to keep him out of the boy's life, this is a love letter to a child he fears will never really know him. It has nothing to do with "scoring".