Curators have delved into the archives to tell the story of fan-led media and show how the spirit of DIY is still alive and well in the modern game

By Drew Whitworth

July 14, 2025

In 1976, Cees Hamelink published a brief but influential article in the Journal of Communication entitled “An Alternative To News”. He asserted the need for communities of all kinds to use the power of print and broadcast media to counter information pushed at them by dominant state and corporate interests. This was not a new argument, as “alternative” media have been around for a long time; 18th century pamphleteers challenged authority effectively enough that many were imprisoned. But Hamelink recognised that these publications were not merely the work of individuals making ephemeral shouts of defiance, but repositories for community memory, media for communicating understandings of the world typically omitted from “authoritative”, official accounts.

For 60 years, the voices of British football supporters have been expressed via the medium of fanzines. But publication, alone, does not turn words into memory. Any message, printed or otherwise, will be lost if it is not archived: not just shoved into a box in a damp attic, either, but safely stored and catalogued so it can be easily retrieved. In this the role of libraries and archivists is essential.

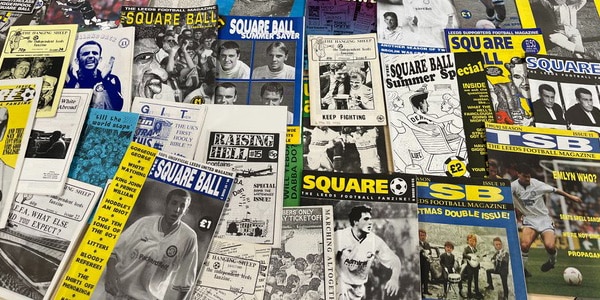

The archivist’s work is currently on show in the Voice of the Fans exhibition at Leeds Central Library, co-produced with the British Library. Its curators suggest The Shamrock may have been Britain’s first football fanzine. With a cover discreetly announcing it as “A Magazine for Celtic Supporters: Price Sixpence”, this 1960s publication supplemented match reports with humour and critiques of football authorities. Unlike other club-specific publications of that time, The Shamrock and its successors were produced not by professional journalists but by fans, willing not only to write but to type, print, cut, staple and then distribute the zine at the next home game.

This DIY ethos was later encouraged by punk, and cultural changes in the sport itself. In a film made by Cole Robinson and commissioned for the exhibition, Paul, the editor of Leeds zine Marching Altogether, recounts how it was a direct response to the early 1980s experience of getting off the bus at Elland Road and stepping into a far-right pamphlet fair. The act of distributing a different perspective was a chance to push back, not just once, but at every home game. “We felt that a fanzine would be a regular way of campaigning against racism at the ground… we talked to thousands of fans every time we had a new edition.”

Fanzines emerged as alternative media not just for particular clubs but marginalised communities, such as LGBTQ+ supporters, and in the women’s game, including Born Kicking, launched in 1990. Felicia Pennant, editor of contemporary football and fashion zine Season, started it in 2016 because “I’d watch football coverage or listen to the radio and realise that there were no people of colour there and no women at all… I wanted to create a safe space where women and marginalised communities could be unapologetic about liking football.”

As a genre, it may seem as if the fanzine’s peak has passed, the challenge posed by the immediacy of other media too strong. Rather than spending half-time reading a zine – or even a traditional programme – spectators are more likely now to head for the bar and catch up with Soccer Saturday. Those who want to vent, whether they were at the game or not, can vlog or tweet without having to worry about who’s stolen the stapler.

Yet more than 60 print fanzines are still published nationwide, from View from the Allotment End, devoted to eighth-tier North Ferriby, all the way to the Premier League. Zines like Brighton’s Dogma and the aforementioned Season are high-quality glossies, but there is still room for more retro publications like Bristol City’s One Team in Bristol (monochrome printing, full-page pisstakes of Rovers) and Burnley’s Der Sönnenkonig (similar, just with a different Rovers).

One Team in Bristol is celebrating its 33rd year. The senior extant publication is Bradford City’s The City Gent, going strong for 40 years. “As long as people still want to write for it, and still want to help me put it together, I’ll keep putting it out,” declares editor Mike Harrison.

Nothing lasts forever, but while fanzines are still being produced, and libraries archive them, the cultural memory of British football fans, and its non-capitalised perspective on the game, uncontrolled by the broadcast media and newspapers, is in good hands.

Voice of the Fans is at Leeds Central Library until August 10. Entry is free

This article first appeared in WSC 455, July/August 2025. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive

Want to see your writing published in WSC? Take a look at our pitching guide and get in touch

Tags: Fanzines