The top division’s mid-table teams simply make up the numbers, so terrified of the drop that they refuse to take other chances to win silverware seriously

14 September ~ “Thank you, John Terry,” is certainly a sentence I never expected to write. But hearing that staying in the Premier League spared Swansea City the risk of hoisting a banner reading “adulterer, narcissist, unreliable witness” this season summarily concluded an internal debate : are you really pleased that we stayed up?

At one level, of course, yes. Nobody wants to go down. The process is agonising, drawn out and generally acrimonious. Decent club employees lose their jobs. Good players leave. There is no guarantee of returning. Moaning about being in the Premier League is, as fans of 72 Football League clubs plus erstwhile rivals such as Leyton Orient, Hartlepool, Tranmere and Wrexham would rightly tell me, the archetypal First World complaint. Future Swans fans will see this as a golden age and marvel at the transformation from lower-league basket case into part of the Premier League’s furniture.

Yet last season’s fight to stay up was an exercise in the seven stages of grief. Acceptance came at West Ham following a game of a rancid quality befitting that ridiculously unfit-for-football stadium whose outcome pointed nowhere but the Championship. And would that really be so bad? The Championship is most things the Premier League claims to be, but is not: competitive, unpredictable and throwing up unlikely contenders regularly, rather than once-in-a-generation. Late-season excitement may mean success rather than the relegation battle it implies in the top flight.

It offered new places to go – Burton, and, it seemed likely at the time, Fleetwood – plus much-missed trips such as Ipswich. True, there would also be visits to Cardiff and Millwall, but at least as full participants in the league rather than the “opponents” we are, in boxing parlance, in the top division.

But instead it is back, in First World complaint mode, for a seventh successive season to the Emirates, Old Trafford, Anfield and the “Bet365” – any novelty long gone – and to an eco-system where our role is well defined and slightly diminished.

Consistently near the bottom for live televised games and, until last season’s defensive chaos produced loads of goals, a good bet for last on Match of the Day, we know our Q-rating with the paymasters. The role as the league’s bright young overachievers has long, and inevitably, gone south – first to Southampton and then Bournemouth.

Every club experience is different, and so colours perception, but it is not hard to imagine echoes of these feelings at West Ham, Stoke and West Brom, accentuated by living memory of having been both real contenders and admired for their football. Southampton may still be tantalised by the apparent possibility of real success while Burnley, Watford, Bournemouth and Crystal Palace are presumably still enjoying the ride.

But all inhabit the same limbo, below a glass ceiling with the likeliest movement downwards. It is a systemic problem, rooted in the Premier League’s all-but impermeable hierarchies. It drives clubs inexorably towards prioritising survival over any other object. And given how far this determines livelihoods, you can’t blame them.

Yet this not only leads to monotony, but also brings its own risks. Swansea’s recent decline began when, instead of being the happy outcome of getting things right, Premier League status became the sole objective. This led inexorably to short-termism – three managerial sackings and a decline in the quality and cohesion of the football – and a takeover, whose mishandling imperilled the defining relationship with the Supporters’ Trust, by owners with no prior connection.

There are now signs of light. Paul Clement echoes Roberto Martínez and Brendan Rodgers as a bright, young(ish), cosmopolitan coach. The restoration of Leon Britton and the signing of Roque Mesa recognised that the “Swansea style” was not some idealistic Barça-light indulgence, but an intelligent, pragmatic approach for a club of comparatively limited means. And if the American owners have yet to convince, they are trying to regain the trust of the Trust.

But the limbo remains. So excitement, except of the relegation survival variety, means taking cups seriously. For all the achievements of six league seasons, the true highlights of the Swans’ Premier League years have come in cups – the League Cup semi-final win at Chelsea, winning the trophy and the Europa League victory at Valencia, all in 2013. These were both unprecedented highs in club history and, like every other cup tie, a break from the routine.

The great betrayers of the modern FA Cup have been the top-flight middle-classes. One of the rare elements of Premier League mythology with any substance is that most clubs do have a shot at anyone in a one-off, but fear-driven failure to pursue this possibility in the FA Cup has handed the competition over to those who care least about it.

Just as Leicester’s title – which was joyfully welcome but addressed the Premier League’s competitive imbalance in the same way that electing President Obama solved the US’s long-term racial inequalities – will be cited as proof of competitiveness for the rest of our lives, so will the alleged lesson of Wigan getting relegated the year they won the FA Cup. But Wigan were not relegated because they won the Cup. Their fate was the one which eventually engulfs any club – ask Sunderland – embroiled in serial relegation fights. And they took a prize and memories to outweigh any relegation.

So keep on thinking long, but not long-ball. Embrace the dream implicit in chasing cups, because football, and football fans, are still about more than balance sheets. And if our number is up – surviving six seasons is already beating the odds – don’t trash the club, as seemed possible last season, on the way down.

Glad? Yes, on balance, even without the Terry factor. But it remains a relative rather than absolute preference. Huw Richards

This article first appeared in WSC 367, September 2017. Subscribers get free access to the complete WSC digital archive – you can find out more details here

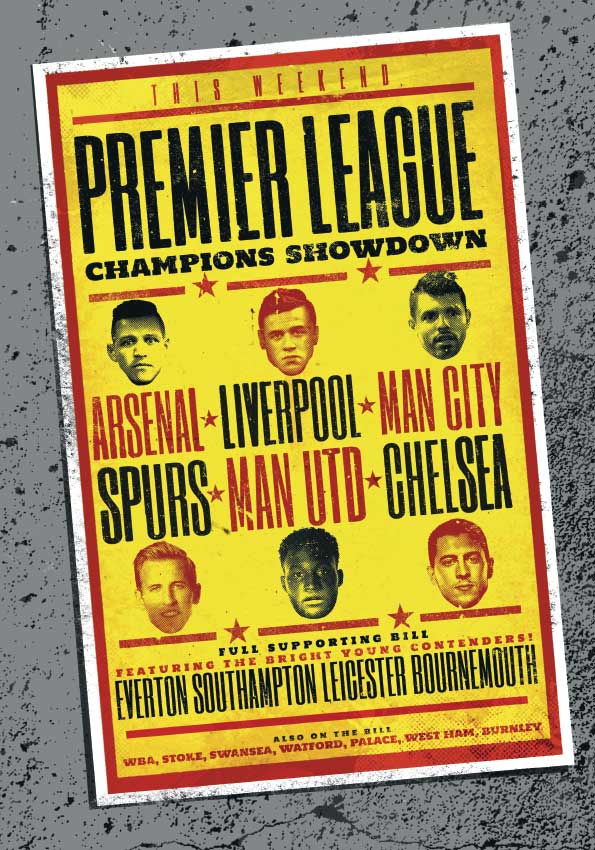

Illustration by Gary Neill