Following a poor refereeing performance, the debate on video replays begins

Following a poor refereeing performance, the debate on video replays begins

Televised football, it is often said, is nothing like the real thing. Yet, despite a setback for the advocates of the use of video replays in refereeing, we may still see it become part of the matchday experience for everyone. FIFA recently decided against sanctioning a first trial of a replay screen in next month’s friendly between Sweden and France, with general secretary Sepp Blatter saying, “We are anxious television doesn’t take over the game.” Sepp must have dozed off a few years ago because the takeover has long since been completed.

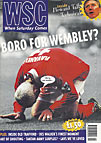

To judge by the inordinate fuss lately kicked up about a particularly bad performance by a member of England’s FIFA panel, the creation of the post of video adjudicator can’t come soon enough. No-one who read a sports section of a newspaper in the last few days of February will have been left in any doubt about the lousy job that Mike Reed made of refereeing the Chelsea v Leicester FA Cup Fifth Round replay, with a clutch of fussy bookings and bizarre free kick decisions culminating in the award of a dubious penalty to Chelsea three minutes from time.

Interminable television replays of the incident proved that no contact had been made; it was terrible luck for Leicester at the end of a furiously contested cup tie and understandable that their players, officials and fans were irate. Millions have been there before them, after all. Every year since football was invented, wrong decisions have crucially influenced the outcome of matches. Occasionally, perhaps more regularly than we would like to believe to judge by recent stories from European cup ties, the referee’s opinion has had a specific monetary value, negotiated before kick-off. In most cases, though, mistakes have been made through poor judgment, pure and simple, but in spite of what FIFA may say now, increasingly powerful forces within football aren’t going to be deterred from their belief that it is possible, desirable in fact, to eliminate such mistakes.

Firstly, as Leicester’s chairman Tom Smeaton demonstrated when referring to Leicester’s “financially very serious” defeat when in calling for the the football authorities urgently to investigate the use of video technology, because the amount of money that can be won and lost on a bad call is deemed to be just too important to ignore; football’s new ‘fans’ in the City are unlikely to tolerate the thought that the value of their new investment can be damaged, at any time, on the say-so of a bank clerk or quality control inspector performing his part-time job.

Secondly, because television’s dominance over the game has given rise to a new cult of perfectionism, ably demonstrated by the Stamford Bridge penalty incident. Sky’s pundits pored over the replays with the intense glee of conspiracy theorists studying newly-found footage of the Kennedy assassination, and asked how much longer football could afford to do without visual aids that could eliminate human error.

Not that the use of television replays would automatically guarantee that the ‘right’ decision is reached in any case: as we see so often, an incident viewed from any number of different angles still can’t produce a consensus amongst those same pundits, who, in arriving at an opinion and sticking by it, are only doing what a referee is required to do in a split second. And opinion would still form a critical part of any system involving the use of video because it would still be down to the referee to decide whether an incident required a second look.

Given that gamesmanship in both serious and trivial forms is already deeply embedded in football, whether it’s a dive for a penalty or just a false claim for a throw in, imagine the chaos that would ensue should players see the benefit of constantly imploring the officials to stop the action and check whether a teammate was held down at a corner, or an opponent was offside when a goal was scored.

Even what is arguably the least controversial use of technology, as a means of deciding whether or not a shot has crossed the goal-line, has fundamental drawbacks. If the lines were rigged up to electronic sensors as in tennis, how would the signal indicating that a ball was over the line reach the referee? If we were to go as far as having referees equipped with radio links, it surely would not stop there – officials would end up being fed a stream of information about the progress of the match so that they’d end up as a little more than automated electrical components.

One dreads to think what effect it might have on the referees’ ability to perform their job should they find their judgment constantly undermined by having to alter a decision. What better way, in fact, could there be to bring about a decline in refereeing standards?

In one respect, however, the introduction of video technology into football could at least be said to be moving with the spirit of the times: the cost of the equipment would surely limit its use to the Premiership and international games. Money would simply be buying a better system of justice for those who could afford it.

From WSC 122 April 1997. What was happening this month