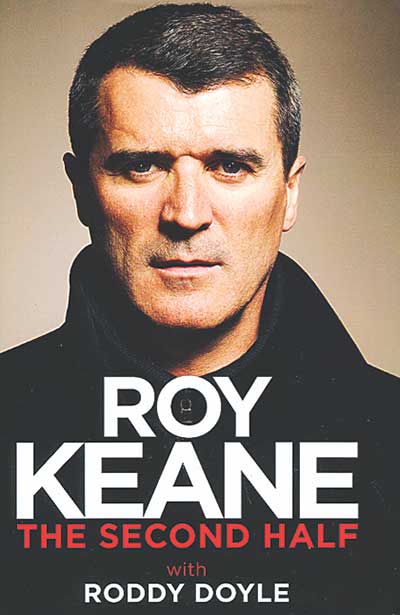

My autobiography

My autobiography

by Roy Keane and Roddy Doyle

W&N, £20

Reviewed by Dave Hannigan

From WSC 335 January 2015

Near the very end of this book, Roy Keane fondly remembers a night at Nottingham Forest when Brian Clough gifted him a £50 note for accompanying him to a charity event. For a 19-year-old neophyte in 1990, that was a substantial sum and the memory stuck with him. Yet, earlier in the narrative, he talks about telling his family they would all have to cut back after he departed Manchester United, by which time his personal fortune was, according to Sunday newspaper rich lists, well north of £20 million.

That sort of inconsistency is rife in these pages, as rife it would seem as it is in Keane’s personality. He hates publicity and craves anonymity yet for the past decade of his life, he has spoken out so often about so many topics that he’s the footballing equivalent of singer/shock merchant Sinead O’Connor. He’s livid at Alex Ferguson for criticising players and being disloyal but, as he trawls through his own managerial stints at Sunderland and Ipswich, he sticks the boot into those who he believes let him down.

If those sort of double-standards are infuriating, this is still a very entertaining account of the subject’s life since the publication of his first autobiography in 2002. Keane is forthright about most (crucially not all) subjects and, as fans of his fast-paced fiction will already know, ghostwriter Roddy Doyle has a wonderful light, comic touch. His handling ensures that this fairly crackles along while offering glimpses of life behind the scenes at Old Trafford, the Stadium of Light and Portman Road.

For all that though there’s something terribly dissatisfying here. Firstly, all the best gags lose their impact because you’ve already read them somewhere else. Secondly, several times you think Keane is finally going to open up about the demons that drive and torment him. Yet he doesn’t. Drink is discussed more than once but by the end of the book you are no nearer understanding the exact nature of his troubled relationship with alcohol.

Strangely for a memoir, he also swerves away from discussing his family. That may be his prerogative but when he makes references to the adverse impact of controversies on his wife and kids, you expect a little more substance about that side of his life. Surely, the very purpose of a serious autobiography is to show the man behind the lazy tabloid caricature.

Even if it is getting tiresome, Keane is still to be commended for having the guts to rail about Ferguson, the game’s most sacred sacred cow. Yet Irish readers in particular will be disappointed he hasn’t a single thing, positive or negative, to say about John Delaney, chief executive of the FAI, and beyond Keane himself, the most controversial figure in the sport in Ireland. Did the current Ireland assistant-manager pull his punches? Or is he learning to be smart when it comes to staying gainfully employed? Like so much else in this book, there remain more questions than answers.