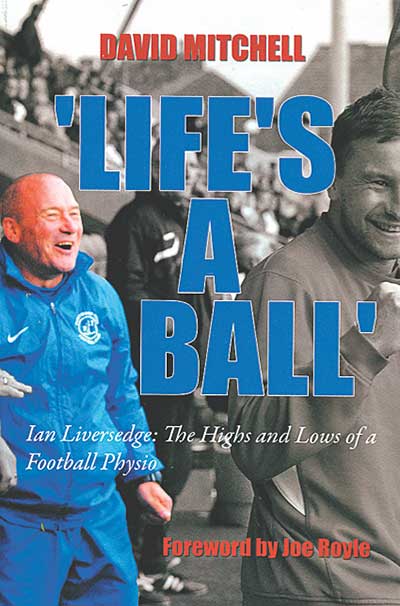

Ian Liversedge: the highs and lows of a football physio

Ian Liversedge: the highs and lows of a football physio

by David Mitchell

AuthorHouse UK, £10.95

Reviewed by Brian Simpson

From WSC 337 March 2015

Ian Liversedge had a long career as an itinerant football physio working for 20 clubs and 15 managers. The highlights are at the margins of his central story as he encounters famous people who played minor roles in his life. As a young player who didn’t make the grade as a pro he experienced the detachment of Everton’s legendary manager Harry Catterick and later encountered Brian Clough, in decline but still gracious in victory. A quote from Kevin Keegan in his playing days at Newcastle goes someway to explaining why striker Imre Varadi was on his way to accumulating 16 clubs: “OK, Varadi has scored 21 goals this season. I’ve set him up to score 60. How many times has he set me up? None. Fact.”

Less well known but vividly drawn is Accrington’s ex-chairman Eric Whalley. He had played for the club, managed them twice, taken a place on the board and eventually bought them. He funded player purchases but fell out with the local council about the cost of yoga classes for the club’s players. A major focus is the ten years Liversedge spent at Oldham from the mid-1980s, where the chalk-and-cheese chemistry of the taciturn Willie Donachie and the garrulous Joe Royle is captured well. His time at Newcastle also gives an insight into the management pairing of Keegan and Arthur Cox, yet very little of this is entirely new.

A desire to pack in as many stories as possible means that some topics don’t get followed up as fully as they might. For example, there are several incidental comments on the changes that have taken place in the treatment and medical care of players, but these are not considered in any coherent way. Some key points are better illustrated by a simple anecdote, such as when the gap between rehabilitation options at elite clubs and the rest is highlighted by noting that at smaller clubs his best option was sometimes to just take players for a walk and a coffee.

Towards the end of the book he describes meeting old friends from football when the conversation rarely touches on the game but is more about “the scrapes” they shared. But drinking exploits are the sort of tales that can only have been funny to those taking part and possibly not even then. Fans who followed Oldham in the period he describes might feel slightly short changed to find that many at the club followed a motto Liversedge characterises as “win or loose, have a booze”.

His description of players’ behaviour, and his own, is at least frank as he acknowledges its impact on his family life. But there is little reflection on whether the behaviour should have a place within any professional sport, nor an understanding of the way it feeds the negative stereotype of football held by many people. In the end, and despite the strengths of the book, his largely uncritical acceptance of some of what he saw or did leaves an impression in places of an opportunity missed.