Producing a fanzine in 1986 was engaging in solidarity with a subculture. But, as Tom Davies argues, while the landscape has changed the issues remain the same

Producing a fanzine in 1986 was engaging in solidarity with a subculture. But, as Tom Davies argues, while the landscape has changed the issues remain the same

Hey, has anyone noticed that some footballers have funny haircuts? Aren’t there are a lot of ugly players in Liverpool’s team? And have you tasted the pies in some away ends? Anyone heard anyone behind them at the match say something particularly stupid or funny lately?

This sounds like the most trite and dated “observational” humour now, but in the mid-to-late-1980s talking about this sort of stuff in print seemed ground-breaking, cutting edge even. Mainstream football writing was stultifyingly one-paced and unquestioning, the game itself widely perceived to be dying as attendances dwindled and the disasters of Heysel and Bradford thwacked the game’s public standing hard, leaving those that followed it feeling pilloried and isolated, another Enemy Within in a divisive decade.

In such a climate even the mere routine of attending a match – particularly an away match – felt like a vaguely subversive act, so when the first wave of fanzines came along celebrating the trivial details of match-going, reading and writing about pies, pints and away tops felt like a defiant, almost political, gesture.

The actual politics of the game were an unmistakable part of the fanzine boom. This was an angry movement – directed at everything from bland matchday programmes, unaccountable chairmen, the creeping over-commercialisation of the game (yes, even then), to the mismanagement of the game at a national level, poor stadium facilities, callous policing and a government whose hostility to football manifested itself in the ID card proposals kiboshed by Hillsborough in 1989. Charton’s Voice of the Valley agitated effectively for a return from Selhurst Park exile, York’s Terrace Talk wanted their home end roofed and Leeds Utd’s Marching Altogether wanted racism driven from their club.

By the end of the 1980s almost every English and Scottish football league club boasted one fanzine, and around half boasted more than one. And if some of the things that exercised fanzines now seem historical curios – plastic pitches, away fan bans, MPs making political capital from hating the game rather than (claiming to) love it – the similarities in grievances are as striking as the differences. Critiques of the Premier League breakaway and the big clubs’ commercial bullying are common enough now but fanzines were pretty much the lone voices of opposition 20-25 years ago, the hastily stapled and clumsily Xeroxed canaries in football’s coalmine.

Crucially, in 1986, football itself felt like much more of a subculture rather than the suffocatingly pervasive “everyone’s-got-an-opinion-on-Torres-to-Chelsea” juggernaut it now is. And fanzines were still a subculture within that subculture, written frequently (but by no means exclusively) by young men of a certain sensibility: reasonably well educated, often as obsessive about music as football – that the fanzine boom began within a decade of punk is significant – and often more widely politically engaged.

But the magazines genuinely generated a sense of being all in this together – editors routinely swapped issues and the morning postbag could provide the breakfast table with scabrous gossip from anywhere from Meadowbank to Man Utd to the lower reaches of the Bundesliga.

What impact did they have? It has been said before that both 1990s lad culture and the apparent “intellectualisation” of the game that developed at the same time had their roots in fanzines, though both stripped out the essential politics. Neither Loaded nor the sort of middle class “new fan” parodied in Charlie Higson’s Fast Show character had any real interest in challenging how the game was run. But fanzines undoubtedly helped broaden how the game was written about, and made doing so profitable. Plenty of journalistic careers took their first steps here.

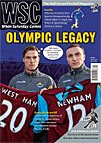

Very few of the first, or any, wave of fanzines still exist now. Just as the development of desktop publishing facilitated the 1980s boom, so the web has negated the perceived need to knock out 40 pages of A5 every month or two. There are, however, some notable survivors. Bradford’s City Gent, one of the very first, is still alive and thriving 27 years on, as is the Leyton Orientear (founded in 1986, and which I edited for three years in the 1990s), and they’re still looking to rock boats. City Gent – never particularly the most venomous of publications back in the day – has been at loggerheads with the powers that be at Valley Parade recently, while the Orientear has played its part in formulating a fan response to the recent Olympic Stadium wrangling.

A loyal readership sustains both. Current City Gent editor Mike Harrison says: “When I took over [in 2004] we only had 50 subscribers and now we have just over 200,” though he cautions: “The fans who buy The City Gent are more middle aged as they’ve grown up buying the fanzine in their 20s and we provide something that they’re used to.” Fanzine production in the 1980s sprang from a youthful demographic often priced out of grounds now.

Fanzines’ descendants are still there, though supporter politics has in many ways become more sophisticated. Blogs such as Twohundredpercent and Andersred dissect the game’s management and finances in a forensic manner that largely eluded their fanzine forebears, while the more politically savvy workings of the supporters’ trust movement have taken the aims of the Football Supporters’ Association in 1985 to the next level.

For ultimately, the anger that fuelled the fanzine boom still exists. Many threats to the game have receded, but plenty of the problems that worried us then have got worse since. So though we cracked some bad jokes, got our spellings wrong, couldn’t lay a page out in a straight line and were a bit full of ourselves at times, when it came to the fundamentals, we were right about a lot of this stuff.

From WSC 290 April 2011