After losing Fernando Torres to Chelsea, Liverpool supporter Rob Hughes explains why player disloyalty is not a new phenomenom

After losing Fernando Torres to Chelsea, Liverpool supporter Rob Hughes explains why player disloyalty is not a new phenomenom

The media circus that trailed Fernando Torres’s move to Chelsea once again raised what is fast becoming a dominant issue in today’s game: club loyalty. Liverpool fans’ dismay was complete when, at his first press conference at Stamford Bridge, their departed idol coolly batted away accusations of traitordom and justified his switch of allegiance by declaring that “romance in football has gone”. Yes, he said, he’d had three good seasons at Liverpool but he wanted to play for a team who actually won things. What’s more, he was never a Reds fan (though, in his defence, he was candid enough to admit he’s no Chelsea nut either). Club loyalty counted for nothing when it came to winning trophies.

You could be forgiven for thinking that this is a new phenomenon. A symptom of the modern era, perhaps. The age of the over-pampered pro, cosseted away from the real world amid bunkers of cash, private estates and a coterie of agents and personal hair stylists. All of which hardly serves to curb the perceived notion of grandstanding egos and their attendant issues of entitlement. Take Wayne Rooney, once a proud Evertonian bearer of a T-shirt reading “Once a Blue, always a Blue”.

Now he wants to quit Man Utd for a club with more investment ambition, before being tempted back by a new deal that would have floated the economies of several small European principalities. Or the influx of players to the cash cow that is Man City. Or even John Terry, routinely cited as a glowing example of monogamy (in football terms, at least) by sticking with the club he’s been with all his life. Never mind his deafening silence during the protracted saga of a potential switch to City in 2009, an episode that only abated once his loyalty had been sealed with the promise of an enormous salary hike.

But the idea of flaky club allegiances is a facet of football that’s far from unique to the modern game. As Harry Redknapp commented in the wake of Chris Hughton’s dismissal by Newcastle, “[It] merely confirms what I have known for ages – in football there is no such thing as loyalty”. It was telling too that one of the first to attempt to defuse the Torres situation was Kenny Dalglish, who reminded everyone of the time when Graeme Souness left Anfield in 1984. It was an age-old issue, he argued, one that wasn’t necessarily governed by a pursuit of trophies. “Footballers will always find a reason to go,” said Dalglish. “Movement is part and parcel of the game.”

As much as we like to think otherwise, ambition has only very rarely been sacrificed for loyalty to one club. Birmingham fans of a certain vintage will remember the day in February 1979 when Trevor Francis – adored by the St Andrew’s faithful for the best part of a decade, ever since signing on as a schoolboy – broke rank by joining Brian Clough at Nottingham Forest for a then unheard of £1 million. His reason for leaving, he was at pains to point out, wasn’t the money. It was all about “advancing my career”.

Similarly, Malcolm Macdonald, long Newcastle’s resident free-scoring flyboy, quit the club in 1976 amid reports of a fractious relationship with manager Gordon Lee. “I looked at all the clubs in the First Division and I highlighted Arsenal as the club I wanted to be at,” he explained. The chances of winning trophies there seemed far more realistic, he went on, “and I wanted to be a part of that”.

You can’t knock someone for being ambitious. Why shouldn’t a player want to leave for somewhere with better prospects, whatever the incentive? One of the lesser known stories – and one that goes some way to refuting the idea of club loyalty as some lost bastion of a more honourable age – involves the great Tom Finney, long considered one of the prime examples of the one-club man. In 1959 he frankly admitted that, even though he regarded his beloved Preston as the greatest club on the planet, if Newcastle were to double his wages, “I would certainly sign for Newcastle”.

Ultimately, players have a freedom that fans don’t. As a supporter, you’re stuck with your club, tied to your institution by a devotion that borders on the familial, urging them on through thick and (in most cases) a whole lot of thin. Decent players, on the other hand, can swap and choose allegiances as they see fit. The only loyalty rests with the fans. It’s why it’s such a valued, not to mention misunderstood, currency in our eyes. And I should know, I’m a Liverpool fan.

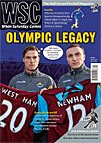

From WSC 290 April 2011