Pitch Publishing, £18.99

Reviewed by Huw Richards

From WSC 426, November/December 2022

Buy the book

Pitch Publishing, £18.99

Reviewed by Huw Richards

From WSC 426, November/December 2022

Buy the book

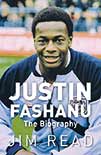

The biography

The biography

by Jim Read

DB Publishing, £14.99

Reviewed by Al Needham

From WSC 307 September 2012

By all accounts, and even by the standards of the pre-AIDS gay subculture of the early 1980s, Nottingham’s La Chic: Part Two was a hell of a club. According to an article in Notts magazine LeftLion: “On a typical night, you might find Su Pollard whooping it up to the latest American imports, while a regal Noelle Gordon wafted around, flanked by stage-door johnnies. You could even avail yourself of the services of a resident chaplain, after you’d made use of the pitch-black sex room.”

The most shocking aspect of the club, however, was that for over two years, it was patronised by one of the country’s best-known young footballers – and it never crossed anyone’s mind to tell the newspapers about it.

Justin Fashanu’s life would have been a seething melange of contradiction even if he’d had the sexual tastes of George Best. Fashanu was a black child raised in a staunchly white community, a born-again Christian (converted in a Nottingham car showroom) in a country that saw that sort of thing as a bit American and odd, and a teetotaller at a workplace where everyone from the boss down went out and got battered. So discovering that he actually preferred other men to the fiancée he’d brought up from Norwich reads like just another contradiction to add to the pile.

As this meticulously researched book spells out, Fashanu was (and is) impossible to pigeonhole. For starters, like his brother, he wasn’t afraid to put himself about, and there’s a great story of him confronting a group of National Front supporters in a pub and breaking the jaw of one of them.

On the other hand, if you’re looking for a stoic sexual-equality pioneer, he wasn’t your man, displaying an arrogant sense of entitlement that put noses severely out of joint, making up affairs with Julie Goodyear and Tory MP Steven Milligan, and using his sexuality to cash in whenever possible.

Crucially, the author could have laid on accusations of institutionalised homophobia with a trowel, but – while making it clear that things are much better now than then – he also points out that the majority of Fashanu’s peers didn’t give a toss who he was shagging, as long as he was playing well. The book also gets as near to the truth of the circumstances surrounding Fashanu’s rape charge in the United States and subsequent suicide in London as readers are ever likely to get.

After you’ve read this extraordinary story – and you should – you can’t help wondering what a 20-year-old Justin Fashanu would be like today. He wouldn’t be the only non-boozer or born-again Christian in the dressing room, he’d be allowed to be as petulant as he liked, and a Twitter feed, invitations to celebrity game shows and Hello and OK sniffing round his house would sate his need for publicity.

But you can’t shake the feeling that there would still be an agent in his ear putting a monetary value on keeping his mouth shut and his trousers on, and a forest of arms brandishing iPhones greeting him outside NG1, Nottingham’s barn-sized gay club. We like to think that, as a society, we’re ready for the next openly gay footballer, but this book spells out exactly why we’ve been waiting so long since the last one.

Cameron Carter analyses the different reactions to football’s many controversies

Cameron Carter analyses the different reactions to football’s many controversiesJust as there must statistically be teatime programmes on the BBC that do not feature Alex Jones or John Barrowman, so we must assume that there are gay footballers out there somewhere in the universe. In Britain’s Gay Footballers (BBC3, January 30), Amal Fashanu, niece of Justin, daughter of John, quested for a gay man among the 4,000 professional players registered in the UK.

Dear WSC

Dear WSC

Howard Pattison (Sign of the times, WSC 286) wonders why there are so few official plaques to footballers in London, but goes on to answer his own question: most of the big names from the pre-war era were based in the north-west, and all the more recent players mentioned in the article died less than 20 years ago. The “20-year rule” – which applies to all suggestions made under the London-wide blue plaques scheme – is designed to ensure that the decision to commemorate an individual is a historical judgement, made with the benefit of hindsight. I could agree that Bobby Moore is as good a case as any for making an exception – but where, then, would you draw the line? The blue plaques scheme is run almost entirely on the basis of public suggestions. In recent years, considerable efforts have been made to increase the hitherto small number of nominations that have come in for sporting figures, including footballers. This has brought some success – Laurie Cunningham and Ebenezer Cobb Morley, the FA’s first secretary and author of the first football rulebook, are now on the shortlist for a blue plaque. As time goes on, more outstanding players and managers will become eligible for consideration, and surely join them. In view of this – and, among other projects, the involvement of English Heritage in the Played in Britain publications and website – the charge that “those who administer our heritage simply don’t see football as part of it” seems about as close to the target as a Geoff Thomas chip.

Howard Spencer, English Heritage