Search: ' Matthew Harding'

Stories

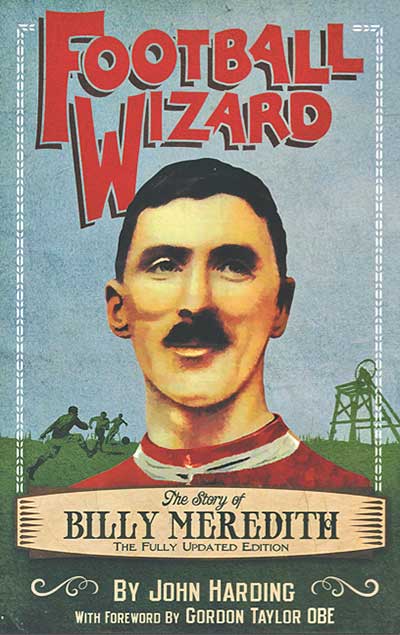

The story of

Billy Meredith

The story of

Billy Meredith

by John Harding

Empire Publications, £16.95

Reviewed by Mike Ticher

From WSC 332 October 2014

If you had to choose one player to encapsulate the Edwardian football world, you would be hard pressed to do better than Billy Meredith. In an extraordinary career, which ended in 1924 FA Cup semi-final defeat at the age of 49, the celebrated Welsh winger was central to many of the era’s key moments.

He scored the winner for Manchester City in the 1904 FA Cup final, then won the League with Manchester United in 1908 and 1911, and claimed another Cup winner’s medal in 1909. He was with United when Old Trafford opened in 1910, and back with City when they moved to Maine Road in 1923.

But Meredith’s greater significance lies in his turbulent relationship with clubs and the football authorities, and his key role in setting up the Players’ Union, the forerunner of the PFA. In 1905 he was suspended for a year after the FA found him guilty (in a closed inquiry) of trying to bribe an Aston Villa player to lose the final game of the season. Incensed by City’s perceived failure to support him, Meredith spilled the beans on bonuses the club had been paying in breach of the recently introduced maximum wage. The case devastated City, sparking the departure of Meredith and several others to United, and cemented Meredith’s hostility to the hypocrisy of the system, as well as personal bitterness over money that would last until he died, a poor man, in 1958.

The suspension helped drive Meredith to re-establish the union, which collided head-on with the FA in 1909, when the whole United team was suspended for refusing to sign contracts that effectively meant disowning the union. Its fledgling power was broken, but its structure survived to give birth to the PFA, which finally defeated the maximum wage and the iniquitous retain-and-transfer system in the early 1960s. As the postscript to John Harding’s book notes, it was not until the Bosman ruling that Meredith’s full vision of contract freedom was realised.

As if all that were not enough, Meredith was also involved, though not implicated, in the 1915 fixed match between Liverpool and Manchester United, for which eight players received life bans – the final scandalous blast of United’s years as a “rebel” club of stubbornly confrontational players.

Harding’s groundbreaking biography was first published in 1985, and has worn well with little amendment. Without over-elaborating, he sketches a rounded portrait of Meredith’s complex personality, rooted in his Methodist upbringing in the mining village of Chirk. Meredith’s rigorous attitudes to fitness, work, industrial solidarity, Welsh nationalism and alcohol (he was a teetotaller, despite running pubs in retirement) are neatly teased out in that context.

But there is still room for a fascinating broader picture of Manchester football in a tempestuous phase of its development, and thoughts on how Meredith’s playing style meshed with the tactics of the day – in curmudgeonly old age he scorned the new-fangled ways of whippersnappers such as Stanley Matthews.

Meredith complained that the Edwardian FA treated the professional footballer as “a mere boy, or a sensible machine or a trained animal”. Harding’s work is far from a dry polemic or hagiography, but a timely reminder of how the players’ struggle to overcome that contemptuous attitude began.

For half a century, celebrities have risked making fools of themselves with no need for reality TV, by playing football. But, as John Harding explains, it’s all in a good cause

For half a century, celebrities have risked making fools of themselves with no need for reality TV, by playing football. But, as John Harding explains, it’s all in a good cause

The lure of the football pitch for theatre folk has always been strong. Ever since professional football became a mass working-class attraction, variety artists have craved some of the allure attached to the game. Before the First World War, comedian George Robey, “The Prime Minister of Mirth”, organised charity fund-raising matches involving top football stars and music-hall favourites, which drew large crowds. After the war, the tradition continued in intermittent form with teams representing actors, the cinema trade and pantomime artists, dance bands and the pioneering women’s team, Dick, Kerr’s Ladies.

Dear WSC

Dear WSC

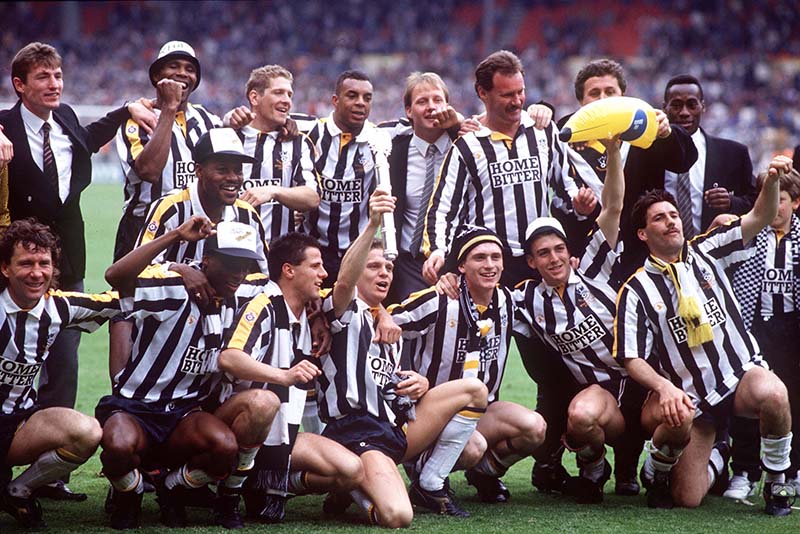

Harry Pearson’s review of Farewell But Not Goodbye (WSC 224) is to be applauded for refraining from trotting out the usual platitudes when the words “Sir Bobby Robson”, “beloved” and “Newcastle United” appear anywhere near each other. While there is no doubt Robson is, and always has been, a Newcastle fan, unlike others who jump on and off the black ’n’ white bandwagon, the fact is that he turned down the chance to manage Newcastle at least five times. Indeed, he even refused to come to Newcastle when his Barcelona job title was the equivalent of dogsbody. What might have been achieved had he jumped at his “dream job” when first offered is a matter of great debate on Tyneside. There is absolutely no argument that he pulled Newcastle back from the brink and for a while established us as a major European force. However, it should not be forgotten that Sir Bobby was given the chance to work at Newcastle despite his reluctance to do so several times earlier.

Alistair WS Murray, Newcastle Upon Tyne

The former boss of Creation Records, Alan McGee, recalls how Robert Fleck lured him to StaMford Bridge and tells how football rescued him from drugs – or was it the other way round?

The former boss of Creation Records, Alan McGee, recalls how Robert Fleck lured him to StaMford Bridge and tells how football rescued him from drugs – or was it the other way round?

Did you become a Rangers fan solely because of your upbringing? It must have been at the time when Celtic were the dominant club in Scotland.

When you’re seven it comes down to who you hang around with. I was at a Protestant school in the late Sixties. I knew some Celtic fans too but the first league match I was taken to by my dad was to see Rangers – although I actually saw Celtic first, in a pre-season match against Queens Park. We lived near Hampden and they were the local club. I used to watch them too for the first couple of years that I was interested in football. You could go when you were ten and you felt safe with a space of your own in this big ground.